Oct 21, 2012

Argo

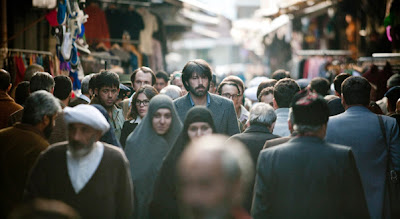

It's a great story, very well told by director/protagonist Ben Affleck, based on the true story of Tony Mendez, who concocted a fake film production in order to rescue out of Iran six American embassy employees who were hiding in the house of the Canadian ambassador, at the time of the Iranian hostage crisis.

The movie starts with a lovely, powerful sequence with storyboards that remind us of that once upon a time, there was a democratically elected Iranian leader, a secular man, who decided to nationalize his country's oil industry. In no time, the US and Britain engineered a coup d'etat and in his place put the Shah Reza Pahlavi, who became a monstrous murderer, thief and torturer. It was this intervention that helped create the Islamic Revolution which deposed the Shah, who was granted asylum in the US and never extradited as his the new regime in Iran justly requested. Today we have to deal with these fundamentalist maniacs thanks to our stellar foreign relations fiascoes such as that one. Times were so different then, before our middle eastern misadventures escalated into 9/11, Iraq and Afghanistan, that it was not inconceivable that producers would want to go shoot a film in Iran just as the Revolution was happening. But truth is stranger than fiction.

Affleck plays Mendez, a stonefaced agent specializing in exfiltration (getting people out of messes), who gets the idea to use a fake movie as a cover, when no other cover will hold. There is much enjoyment to be had in the casting of the great John Goodman as the make up effects artist and CIA helper John Chambers, who helps put the fake production together and the marvelous Alan Arkin as Lester Siegel, an old Hollywood shark. Re Alan Arkin all one can say is that nobody in the business lands their lines with such deadpan aplomb. Everything that comes out of his mouth has perfect, devastating timing. Everything has a delicious zing. Goodman is on screen for like five minutes and almost steals the show. But it is the handling of the material that is most interesting. There is nothing funny about the first part of the movie. The violence is palpable, the hatred of America shot in close up (stellar, unobtrusive, but exciting work by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto), the nerves are frayed. But the moment the Hollywood plan turns up, comedy does too and one wonders if Affleck is going to be able to mesh the tones. Somehow, it works. All the actors are excellent, the jokes land well (except for one they keep repeating over and over), and the movie is very well done, the pacing exciting, the experience thrilling. Affleck is becoming a more confident director with each movie he makes. He greatly underplays plays Mendez as a dry man who is loath to betray feelings. His wooden face as he sits in a negotiation between Arkin and Richard Kind is hilarious. He betrays nothing except for a minuscule flick of recognition, perhaps awe, when Arkin mentions his friend Warren Beatty. This CIA man feels more alien in this meeting than perhaps in any other of his dangerous missions, but he too is impressed by star power. The third act is a nail-biting bit of suspense, including soaring string music (by Alexandre Desplat), just like in the movies, as if to weave the surrealism of the actual story with the fantasy of film. A bit where the fake filmmakers show some Revolutionary guards at the airport the film's storyboards and one of them literally pitches the movie to them in Farsi, with impropmtu sound effects, speaks to the power that stories, and movies, even the most farfetched and ridiculous, have to enthrall an audience. Argo ends too neatly, too happily, like in the movies. It is more of a caper with political sting than an issue movie and it errs on the side of telling a good story, even if it takes liberties, and cuts to the chase, like they do in the movies.

Oct 17, 2012

NYFF 2012: No

This third part of Pablo Larraín's trilogy about Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile is the most approachable and crowd pleasing of them all, if not the most rigorous. The movie that put him on the map, Tony Manero, is a carefully crafted, extremely disturbing look at a sociopathic character, played by the fantastic Alfredo Castro, who is obsessed with impersonating John Travolta at a time when his countrymen are being murdered and tortured. His second movie, Post-Mortem, also starring Castro, is also an unsavory tale about a weird man who is confronted by the ugly reality of his country as his job at the morgue becomes too busy. Throughout the trilogy, Larraín seems consumed by the idea of individual indifference in the face of tyranny.

This final installment, based on a play by Antonio Skármeta, and co-written by Pedro Peirano, the writer director of The Maid and Old Cats), follows the travails of advertising creative René Saavedra (a wonderful Gael García Bernal), as he reluctantly decides to help the Chilean opposition craft a TV campaign in order to win a referendum in the last years of that brutal regime. The US, after helping Pinochet gain power by orchestrating a coup d'etat against Salvador Allende, got qualms about the human rights abuses of Pinochet's 15-year dictatorship and pressured for a referendum, the first democratic elections to take place in that country since Pinochet took power. The movie is a fun, although rambling tour into how the opposing campaigns communicated to the Chilean people. "No" means the vote against Pinochet for another term.

Larraín, who has a penchant for stylishly ugly aesthetics, goes all the way by shooting the entire movie in low resolution video, which is what existed in those days. After a while, one gets used to the result, but everything looks hideous. However, this time he stays away from the ugly, violent grotesquerie of his other two films.

René's boss is a Pinochet sympathizer and rich bastard, played by the chamaleonlike Castro, whose agency helps the regime, because he actually supports it ideologically. It's a fun fight between two creative minds, and not necessarily between opposing ideologies, but between young and fresh, and conservative and hanging on to power by whatever means possible. René's boss likes to threaten and harass, much like the regime he represents.

Larraín gets the dynamics and milieu of advertising just right. Very much fun is watching René always use the same bullshit spiel ("Chilean society is ready for this") to sell different campaigns to different clients, regardless of the product. He is not concerned with ideology. He cares about image and fun looking spectacle and the kind of idiotic ads that somehow move a lot of product. The movie starts with an outrageous commercial for a cola called "Free", so hilariously tacky that not even an imaginative director like Larraín could have come up with it as a parody. Larraín uses actual footage of brutally squelched demonstrations, Pinochet ads, opposition ads, and the commercials of the era and intersperses them with the story of René, in which actual leaders of the opposition movement appear, including Patricio Aylwin, the man who eventually won the election. The choice to unify the quality of the video to the actual footage pays off, even as one's eyes suffer, making the movie seem as real and in the historic moment as possible.

René fights the tendency of the opposition to sound like martyrs and recite the catalogue of horrors under Pinochet's murderous regime. He instinctively understands that even though it may all be true, people don't want to hear it. It dispirits them and makes them afraid to vote against such a well oiled repressive machine. Instead, he fights Pinochet with rainbows, young people dancing on the streets and Chileans eating baguettes at picnics (unrealistic, but it looks pretty, which is what matters). His clients feel this is offensive, but what choice do they have? Since the law is that each party has 15 minutes a night (an eternity) to present a platform, the No party allows René to do his rainbows and "We are the world" ripoffs, but they also sneak in some powerful truth telling ads. Meanwhile, on the other side, the debate hinges upon whether the Generalissimo should always appear in his medal bedecked uniform or wear civilian clothes. When they decide to poke fun at the rainbows and the happy dancing, it backfires, since as René knows, the audience hates negative reinforcement. As he sees himself losing the battle against frivolity and optimism, René's boss bitterly muses that the "Yes" campaign has too many military men, too many fat military wives, too many parades and uniforms. It is as stale and putrid as can be, as befits where it comes from.

Larrain is a great satirist and in No he lets loose and spends a lot of time going from one campaign to the other, and including a lot of fascinating original footage, but which unfortunately makes the energy of the movie flag. Still, No is a very engaging, original, smart film about a man that ends up doing something heroic for his country without really wanting to; an unlikely hero without principles, except that of doing what he knows to do best. García Bernal's stunned reaction to the results of the election, his gradual overcoming with emotion as he goes out into the streets anonymously and the enormity of what happened seeps in, is a gorgeous piece of silent acting. There is great joy at Pinochet's defeat but the movie ends in a bittersweet note as René goes back to selling bullshit, a changed man. The question is whether Chile has really changed with him.

NYFF 2012: The Gatekeepers

This intense, intelligent, eye-opening documentary by Israeli cinematographer Dror Moreh is a series of interviews with six ex-heads of the Shin Bet, the Israeli Security Service. The candor with which Yuval Diskin, Avraham Shalom, Avi Dichter, Yaacov Peri, Carmi Gilon and Ami Ayalon speak, may be shocking for those who insist on looking at the occupation as ignorable historic fallout, or worse, as a security buffer or a messianic calling. These men, who have patrolled the occupied territories and spoken with many Palestinians, are as blunt about their unsavory activities, as about their reckoning of the grave mistake of maintaining the occupation. They ensure Israel's survival by recruiting Palestinians to be informers against terrorists, elicit information from prisoners through harassment techniques short of violent torture, and constantly make decisions to kill targets. Their years of tough experience have led them to believe that the current policies of the State of Israel are leading it towards extinction. They should know.

The film is a crash course on Middle East geopolitics, starting from the Six Day War in 1967, in which Israel conquered the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, after a concerted attack by neighboring Arab countries. This created a Palestinian refugee problem that has become an untenable thorn on the side of Israel and threatens its survival.

The endless, nauseating cycle of violence on both sides is shown with shocking footage of the bloody aftermath of suicide bombings, Israeli tanks razing homes in Gaza, major riots in the two Intifadas, and even some footage of targeted assassinations. The cumulative effect of the carnage on both sides not only makes one queasy, it makes one question the effectiveness of endless retaliation. It's barbaric.

The heads of the Shin Bet like well executed, clean plans in which they kill their targets without harming anyone else. One of their best efforts involved a remotely controlled cellphone that had explosives inside. How they managed to make it available to an important terrorist leader, they don't specify. But as one of them says (looking like the sweetest grandpa in the world), there's nothing better than a clean hit. Unfortunately, clean hits don't always happen. Things are rarely clean, and even more rarely black and white. One of them criticizes American drone attacks in Afghanistan: you target a wedding, you kill everybody around, and you don't even know if the target was actually there. They talk about issues that currently plague the Obama administration, but that nobody in this country is interested in airing, such as drone attacks, collateral damage in targeted assassinations, the use of torture and the pointless escalation of war.

They offer candid explanations of successful missions as well as of terrible blunders. They go into detail about a complex operation designed to take out several important terrorist leaders in Gaza, an operation that because of political pressure, compromised the amount of tonnage they needed to pulverize the house the targets were meeting in, thus allowing all the targets to walk out of the rubble on their own two feet, as one describes it. But they also had to disarm and neutralize a dangerous religious fringe group known as the Jewish Underground, which intended to blow up the Dome of The Rock, the third holiest place in the Muslim world. They prevented the worst Middle East crisis of all time, if not a global conflict, and sent these maniacs to jail, only to see their sentences shortened by the right-wing Likud government. One of them thinks that the worst threat to Israel's survival is not the enemy without, but the messianic, Biblical fringe groups that are supported by the current Bibi regime, which continues populating religious settlements.

The Shin Bet leaders are not gung-ho ideological bullies. They have to be great pragmatists and weigh every option, looking for all kinds of political and human fallout. Their experience has made them see the occupation in a different way. They all want out. Since Israel is a democracy with legal institutions, some of them had to resign after terrorists who were captured alive were beaten to death by soldiers, or when they botched operations, harming innocent Palestinian civilians. They concede they were unable to prevent the unprecedented assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at the hands of a religious punk. Moreh pointedly shows the horrifying anti-Rabin incitement propaganda created by the far right, which is reminiscent of Nazi propaganda. In fact, Abraham Shalom, one of the most ruthless Shin Bet leaders, even says that the occupation reminds him of the Nazi army. He is careful to distinguish between the extermination of the Jews, to the occupation of Europe by the Germans, which is what the occupation reminds him of. But that these words come out of the mouth of an ex-director of the Shin Bet is unprecedented. In the Q&A after the show, Moreh explained that Shalom was a survivor of the Nazis. Apparently, he was also in charge of the operation that brought Adolf Eichmann to trial in Israel. That Moreh chose not to include this as a justification for Shalom's comment and his ruthlessness defending Israel, shows how tough minded the filmmaker is in his pursuit of changing the status quo. One of the ex-directors says "we have become cruel". It is the unvarnished truth, and it hurts. This is not what Israel was meant to be.

The Gatekeepers shares the political agenda of these men, who have come out publicly to voice their concern about the direction Israel is taking, in which nothing is being done, if not exacerbate an already explosive situation, in order to ease the burden of the occupation for both sides. They all feel contempt for the Israeli political leadership regardless of ideology, which only calculates the collateral damage of public opinion and panders to fear. At the beginning of the film, one of them says that before any operation, the Shin Bet offers the politicians several carefully considered options, but politicians see things in black and white. They only want to know: to do it or not to do it? As they bear witness, it is much more complicated than that.

What is astounding about this film, beside the candor with which the men speak, unthinkable here in the "land of freedom" that is the US; is that all of them, regardless of their ideology, are unequivocally against more Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, all of them are for a Palestinian state, and all of them are willing to talk to absolutely any enemy, no matter how hateful, brutal and irrational (including Hamas, Ahmadinejad, etc) to inch peace forward. At times, they sound like they almost pine for the likes of Yassir Arafat, now that Israel has to deal with crazier fundamentalist enemies. After all their bloody efforts, they are convinced that talking and listening are the only way.

This taut, gripping, powerful documentary is required viewing for anybody who claims to support Israel as well as for anybody who wants to get a closer look at the complex geopolitical reality of the area. It's not pretty, it's not reassuring, it's shocking and tough as nails, but it is essential.

Oct 15, 2012

NYFF 2012: The Ones That Got Away

Yesterday was my last day at the 50th New York Film Festival and I was invigorated and not at all tired after 22 movies, perhaps because I saw mostly extraordinary films.

But, as is to be expected, there were some clunkers, all of which my instincts had correctly warned me against. There were no truly offensive movies, but the three French movies I saw (not counting Amour) were very disappointing.

Camille Rewinds by Noemie Lvovsky is a French remake of Peggy Sue Got Married that does not improve on the original. It is rambling and not very disciplined, although it has some funny moments.

About my violent impatience with You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet, the latest outing by Alain Resnais, you can read here. It was the worst movie I saw in the festival.

Also disappointing was Olivier Assayas' Something In The Air, an autobiographical account of his radical high school days. Assayas is an energetic, exciting filmmaker, as he amply demonstrated with Carlos, but here he chooses to use sulking non-actors for the main roles and all the energy he puts into the staging, his untalented cast saps from the film, making it extremely tedious. They look the part of French students in the seventies but they are morose, and unintelligible young people without personalities. It's hard to care for their conundrums. Assayas has a great sense of atmosphere and has much to criticize of idiotic student politics, drug use and bad French taste in pop music. As in Carlos, a vastly superior film, he continues coldly skewering dogmatic ideologues with his refreshing lack of patience for antiquated leftist clichés. I'm glad I stayed until the end because the best scene in the film comes late in the movie and involves the shoot of a movie starring Nazis, a prehistoric bimbo and a dinosaur. But it takes Assayas way too long to get to the point; namely, that art and creativity and even working on the cheesiest film on Earth are a better, more genuine calling than being an aimless young French bourgeois toying with ideas of revolution.

Sally Potter, whose films I have never liked, did not disappoint with Ginger and Rosa, which is pretty bad. The only reason I bought tickets was the cast, which promised the great Timothy Spall, Annette Bening, and Oliver Platt, only to waste them in puny roles. The main roles are mostly miscast, with a truly awful Christina Hendricks playing Ginger's mom, Alessandro Nivola, misdirected, playing her dad and a good, lovely Elle Fanning playing Ginger. Why Potter couldn't find actual British actors to play these roles is beyond me, but you could feel the strain in the actors grappling with the accents (with Fanning faring best of all). The movie is an obvious and labored melodrama with artistic pretentions, whose beautiful cinematography reminds one of expensive TV commercials. Potter lets her actors flounder, can't direct her way out of a paper bag, can't stage a scene for the life of her, her scenes are mostly vignettes that end nowhere, and her thesis about a British teenager coming of age in the sixties while obsessed with nuclear annihilation is obvious and strained. The festival's organizers don't do Potter any favors by including such a mediocre, bumbling film amongst such quality company. There were first films by directors from Mexico, China and Israel that showed much more discipline and rigor than this half-baked exercise in melodrama. Ginger and Rosa is like a Mexican soap with fake British accents. Dreadful.

The Dead Man and Being Happy, an Argentinian film by Spanish filmmaker Javier Rebollo, is an interesting concept marred by way too much cleverness. It's a road movie starring an old hit man and a younger woman, who drive around Argentina as he waits to die from three inoperable tumors. There is fun observation of some of Argentina's most endearing quirks, like sheltering Nazis and being always on the verge of development or disaster, usually both at once, but it's all marred by a really annoying, mostly unfunny and unnecessary voiceover narration that aims for drollness but is redundant and pretentious. Still, there is something oddly appealing about the adventure, even if it is contrived. I guess it's the travelogue aspect of it. Nothing that Lucrecia Martel hasn't done a million times better.

Here are our favorite NYFF films top down:

Extraordinary

Amour Michael Haneke

Caesar Must Die! Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

Like Someone in Love Abbas Kiarostami

Beyond The Hills Christian Mungiu

The Gatekeepers Dror Moreh

Excellent

Barbara Christian Petzold

Tabu Miguel Gomez

Fill The Void Rama Burshtein

Very Good

Frances Ha Noah Baumbach

Our Children Joachim Lafosse

No Pablo Larrain

Good

Final Cut Gyorgy Palfi

Here and There Antonio Méndez Esparza

Memories, Look at Me Song Fang

Bwakaw Jun Robles Lana

Disappointing

Something in The Air Olivier Assayas

Camille Rewinds Noemi Lvovsky

Annoying, but Interesting

The Dead Man and Being Happy Javier Rebollo

Room 237 Rodney Ascher

Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Marina Zenovich

Dreadful

Ginger and Rosa Sally Potter

You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Alain Resnais

Stay tuned for more reviews of the Festival coming soon.

Oct 11, 2012

NYFF 2012: Like Someone in Love

Abbas Kiarostami is back to form in this jewel of a movie set in Japan. This is the second film he makes outside of Iran. His last, Certified Copy, with Juliette Binoche, felt like a clunky conceptual exercise. But Like Someone in Love is much more accomplished and heartfelt. The movie starts with a 14-minute scene in a bar in Tokio, in classic Kiarostami style. We hear a conversation, we don't quite see who's talking, but we have plenty of time to immerse ourselves in the milieu and find out who the movie is about. A young woman is protesting to her jealous boyfriend on the phone that she is with a friend. She is not lying. The friend is there, yet at another table. Through different clues, we discover that she's a young call girl and her pimp (a man who has been hovering in the background, talking to customers), asks her to go see a special client on the outskirts of town. She doesn't want to go. She claims her grandmother is in town and she has to study for her exams, which he dismisses as lame excuses. She wants him to send her friend, who is more feisty and seems more used to the line of work, but he insists it has to be her. She screams at him, but she ends up obeying. He puts her in a cab and off she goes. We get a glimpse of Tokio at night from her point of view, but Kiarostami focuses on her crushing sadness as she listens to several long messages her grandma has left her, trying to get to see her. She is there for the day and her train leaves at 10:30. It's not too late, so the girl asks the driver to drive by the station, where she sees her grandma waiting outside, as she has done for hours, hoping to see her. But she doesn't stop. Kiarostami encapsulates the entire history of the girl (and a good chunk of Japanese culture) on this car ride. Her shame at seeing her grandma, who knows she is a college student, but not a call girl, the fact that she comes from a small town, and she is not like the other small town girls who stayed put and are getting married, according to granny's gossip on the answering machine. It is the height of simplicity and great writing, and it is heartbreaking.

Her mystery customer turns out to be a courteous old man, a literature professor with a taste for Ella Fitzgerald. The movie is about how their random connection develops into a complex bond.

Surprisingly, the minute she arrives, she stops moping and turns on the charm and good manners that modern geishas are expected to have. But she seems sincere. She feels at ease with this man, who no doubt reminds her of her grandma, whom she brings up casually in conversation, as if talking about her could ease the pain of her avoidance. The professor has set an elegant table, made dinner and chilled some champagne. But she goes to the bedroom and undresses, off camera, alarming the old man, who wants to have a civilized evening first, and maybe even last. She falls asleep in his bed. He becomes entangled in this girl's life, with her jealous bully of a boyfriend. Like Someone In Love explores different kinds of love, from love for sale, to ancient unrequited love, to obsessive possessiveness, to filial love, to familiar duty and devotion. In the end, the lives of this unlikely couple intersect, crashing into each other. Kiarostami, working with the added challenge of an alien culture with a different language, is in complete command of his storytelling powers. The movie reminded me of the short stories of Anton Chekhov. It shares Chekhov's wise, poignant observation of people's troubles, a gentle humor but also great sadness. Everybody in the movie is somehow bruised and saved by love. The writing is superb, providing vast panoramas about people's lives in just a few strokes of dialogue. Kiarostami is the undisputed master of shooting inside a car. He makes it look fluid and effortless, and in his hands, the interior of a car becomes a perfect stage for human experience. Like Someone in Love is a tender, sharp, luminous film.

Oct 9, 2012

NYFF 2012: Beyond The Hills

My friend Tony christened this movie Brokeback Mountain Meets The Exorcist, which is pretty accurate, if sarcastic. Tony didn't like this powerful film by Cristian Mungiu, but I think it's even better than his 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days. At two and a half hours long, I was never less than transfixed by the complex story it tells, loosely based on a true story. Two grown orphans (as you remember, Romania is rife with unwanted children due to the monstrous legacy of Ceaucescu), meet at a train station. Voichita has become a nun in a fringe Russian Orthodox convent, Alina has come back from working in Germany, where she is lonely and miserable, and she wants to take her best friend with her. Voichita and Alina seem to have been a couple in the past and they miss each other terribly. But Voichita is now devoted to God, and under the spell of a priest who runs this place without electricity in contemporary times. She has found a community where she is cared for and where she doesn't have to deal with the horror of Romanian life outside its walls. Meanwhile, Alina, who has been unhappy in a foster home and working abroad, just wants her lover back, which is now impossible since Voichita is now a nun, and shuns her sexually. Alina's plan is that Voichita will come to Germany to work with her on a boat. But Voichita doesn't want to leave. She'd much rather give Alina a home in the convent, hoping she can find peace in God, to which Alina reacts by trying to throw herself down a well. The movie is the tug of war between the strong needs of the two women. They love each other, but Voichita cannot fathom leaving her new calling and Alina is not one to allow religious mumbo jumbo to take root in her soul. All she wants is to be with the woman she loves, and she acts like a bull in a China shop when she can't make it happen. Mungiu draws interesting parallels between the ministrations of psychiatric science (Alina ends in the hospital, which, like everywhere else she's been, rejects her and sends her back to the convent), and the exorcisms of religion, both trying to cure a girl from her own love. Religion has taken her lover from her and she is wary and skeptical of it, since it has never helped her in the least. But since she will do anything to be near Voichita, she tries to fit in the convent, and after Voichita's intercessions on her behalf, is accepted at the convent on condition that she submit to bizarre confessions and penances, according to the orders of the priest, who can recognize trouble when he sees it. Used to a dozen of meek, obedient women who call him Papa, Alina is a threat to the grip he has on the place. In fact, the first words that come out of his mouth when Voichita asks him to let her go to Germany with Alina for a few weeks, are in exact opposition to what Jesus would have done when faced with the same request.

In my view (I had endless arguments with a couple of fellow moviegoers after the movie), he is a calculating bastard and a classic cult leader. My companions felt he was sincere in his belief and was somehow trying to help Alina literally get rid of her demons. Mungiu gives enough clues throughout the movie to present him as a con man. Yet he doesn't make him a moustache twirling villain, but a paternal figure that seems to mete out concern, justice and monolithic authority in equal measure. He has given shelter to desperate women, and he doesn't use them as a harem, but his power lies in the total control of their fates. I love this movie because it is one of the most powerful anti-religious films I've ever seen, and God knows there are not enough of those around.

Regardless of my sympathy towards Mungiu's devastating assessment of the distorsion and debasement of personal faith into superstition, the movie is one of the most impressive directorial feats I've seen in a long time. I have rarely seen a movie that crams so much essential information in each frame, both visually and in the dialogue. Mungiu won the award for best screenplay at Cannes, and deservedly so (in a year against strong contenders like Haneke's Amour and Kiarostami's Like Someone in Love). Context, nuance and ambiguity are handled through casual conversations among secondary characters, and what we learn about the reality of these two young women is harrowing. A couple of times Mungiu delivers mortal blows of reality that take your breath away with just one line of dialogue. He seamlessly handles several concurrent layers of reality: the love story of the women, their past, present, and possible future, the microcosm of the convent and the pull of Romanian society at large. He works in long, masterfully choreographed single takes, crammed with activity, every scene sharp, clear and essential. The takes are long in that they are not divided by cuts, but they whizz by, bursting with life and energy, even if half the time the energy is heavy and faintly malevolent. This is a much harder way to work than relying on editing cuts, coverage and different angles, but it gives the film a strong sense of place, and an intense, realistic immediacy. His work with the actors is equally brilliant. Cosmina Stratan (Voichita) and Cristina Flutur (Alina), who shared the best acting prize at Cannes, are extraordinary. Opposite in temperament, they don't say much, but each one has tremendous power in her own convictions. Flutur is heartbreaking as a woman wild with love and rage. Stratan, equally powerful in her meek sweetness, undergoes a silent change of heart she communicates with the sheer expression in her face, which after two hours of gentleness, becomes a hard mask of devastating recognition. They are both astounding.

Mungiu portrays a Romania rife with incompetent bureaucracy and appalling social indifference. Whether it's filthy photographers taking indecent shots of teenage orphans (one of the essential pieces of information delivered casually), or foster parents who seem charitable but are moved by self-interest, one can understand that two young orphans sent out into this society need to escape it, each in her own way. This intense, multi-layered film is a parable of Christlike suffering and sacrifice, a scathing indictment of blind faith, and a critical look at a broken society that seems to be flirting with modernity but is still mired in regression and traumatized by years under a depraved communist dictatorship. Beyond The Hills is a harrowing but highly rewarding film.

Oct 8, 2012

NYFF 2012: Amour

Do not be fooled by the romantic-sounding title of the latest Michael Haneke film.

Amour, a masterpiece, is as tough and devastating as any of his other films, and then some. It is an intimate look at the end of life, the ugliness of illness and death, and the devotion of love.

An epic movie that takes place mainly in one apartment, with just a handful of characters, Amour is a film from which it is very hard to recover. Haneke has a streak of the stern educator, who insists on showing the darkest aspects of human nature, as clearly, ruthlessly and devastatingly as possible, in the service of opening our eyes. So Amour, which is about love, may sound like Haneke has softened his stance, or allowed his gimlet eye to cloud. Never fear. He pulls no punches in telling this most universal of stories, the one narrative thread that comes for us all.

Amour's depiction of the bonds of love is beyond touching, it is emotionally devastating.

There is not one scene in this movie that seeks to make it easier for the characters, much less the audience, to deal with the terrifying prospect of decay and death. This is above all, a movie about human dignity. After all, isn't dignity the end result of love? This is borne by the clarity, intelligence, and the profound sympathy with which Haneke depicts the difficult rite of passage of his characters towards death. Yet he refuses to sentimentalize, cheapen, ingratiate, mythify, or gloss over the subject. I'm offended by movies in which people with terminal illnesses decide to have the time of their lives while they wait for death to come. I find them preposterous, deceitful and naive. There may be a lucky few who die in their sleep with a dreamy expression on their faces; most people are painfully conscious of their illness as a terrible burden for their loved ones. Most people are too sick to decide anything, to frail to be in peace. The loss of their capacities, their impotence against their own demise, is a source, not of expectant bliss, but of anger, depression and shame. Amour is a cleansing experience. It redresses the cinematic fallacies of death in the movies, and it ennobles us through the heroic determination of its characters to cling to their human dignity. It is also, probably, the best anti-Hollywood film of all time in the sense that it subverts the cheapened definition of heroism in movies. You want heroes? You can find them here -- far more heroic and larger than life than any guy in tights -- in two impossibly elegant, beautiful octogenarians, transcendently played by Emanuelle Riva and Jean Louis Trintignant.

The astonishing opening scene shows firemen forcing open the door of an elegant apartment where a death has taken place. Doors and windows have been sealed with masking tape. It's been days, so everyone covers their faces from the stench. An elderly woman's body is found, blue and withered, her pillow strewn with flowers. Next comes a long take of an audience at a concert hall, mirroring us. What we are about to see is a reflection of our own life. Among this audience sits an elegant couple, alert, waiting for the music to begin. They come home bantering courteously. After all these years, he still finds a bon mot to tell her. Georges and Anne are a refined Parisian couple. They have devoted their life to teach music. They live surrounded by civilization: books, art, Paris. They are warm but quaintly formal towards each other, and they quietly enjoy their long lived company.

But Anne has a stroke. The first movement (in this movie the acts feel like movements in a sonata), takes place at the beginning of her illness. At this point, Anne is still lucid, yet paralyzed on one side. It's a scary nuisance, but she is fiercely independent and refuses to be condescended to. She has been to the hospital and makes Georges promise he won't send her back. The movie is about how he keeps this promise.

In the second movement, Anne deteriorates, losing her ability to speak and do things for herself. However, her mind is still painfully intact, and Anne, the most elegant and dignified of women, cannot stand her dependency and the loss of her physical integrity. She is depressed and angry. Throughout, Georges soldiers on, taking care of her by never losing sight of the woman she has always been. He is an intelligent, articulate man, dry and loving at the same time, who honors his promise without complaint, without self-pity or aggrandizement, and without expecting applause, yet with great tact and delicacy towards his wife. No words suffice to sing Riva's and Trintignant's praises. Haneke is not one to spare his actors the discomfort of portraying the most unvarnished truth. Riva and Trintignant rise to the occasion with extraordinary intelligence and generosity, without a trace of pandering sentiment or manipulative emotion. At their age, to portray these characters with such commitment, artistry and dignity is simply epic.

There is a daughter (Isabelle Huppert), who waltzes in from time to time, cries and expresses concern, but is no help at all. Georges hires a nurse who, like many nurses, is equipped with miraculous kindness. But as Anne deteriorates, he needs to hire a second nurse. This nurse is not kind. She combs Anne's hair like a child abusing a doll. She then forces Anne to look at herself in the mirror, patronizing her like a child, falsely insisting that she is beautiful. This incident is appalling: an intelligent, independent woman, trapped in an unresponsive body, at the mercy of an ignorant, indifferent and slightly sadistic nurse. It is a banal kind of sadism, and therefore all the more cruel, since it pretends to pass as care. Georges fires the nurse, and she accuses him of meanness, which is the height of injustice after what he has done for his wife. She also squeezes him for more money. It is revolting, and an example of the kind of harsh emotional violence that Haneke likes to inflict on the audience. But in Amour cruelty is tempered by the grace and thoughtfulness of George's care, by the defiant dignity of Anne, and by the equally unflinching look at the bond between Anne and George.

In the end, Anne's suffering becomes unbearable for both of them. A shocking, violent act of mercy is delivered both by Georges and the director bluntly, but with deliberate care. It is both brutal and civilized, harsh and tender; a beautiful, terrible scene. And so, throughout Amour (as in life, perhaps) we cling to the small yet enormous moments of grace that float like buoys amid the unforgiving waves of suffering. In his last two films, Haneke has allowed mercy and tenderness to take root among his usual explorations of depraved indifference. It started in The White Ribbon, and has fully bloomed in Amour. He happens to be as masterful and unflinching an observer of love as he is of cruelty. Amour is a transcendent film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)