Jul 23, 2012

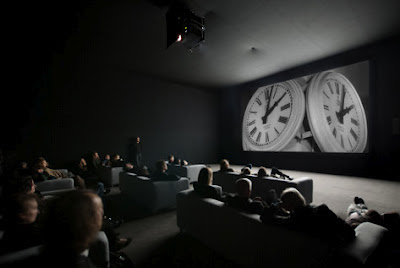

The Clock

Now showing as part of the Lincoln Center Festival, this impressive art installation is well worth braving the endless lines to get in. (It's free). I breezed in last Saturday at 8:30 am but when I came back at 11 pm, I had to wait almost 2 hours to get in. And I intend to go back this week. It's addictive.

Artist Christian Marclay has created a unique timepiece. It's a real-time clock made of movie clips that have to do with time. If you walk in at 8 am, it is 8 am in the clips. A minute later, it is 8:01. It's a movie that lasts 24 hours. What is astonishing is that Marclay found clips that feature either clocks, watches or characters mentioning the time of almost every minute in the day. That's a lot of clips. The Clock is not just a collection of random clips but a flawlessly edited movie that is absolutely spellbinding in many levels.

First level, if you are a movie junkie, you are in heaven, as you recognize faces, favorite stars, scenes from films, even clips from movies you haven't seen, or wonder about actors whose faces elude you, try to place a movie name to a scene. Even if you don't know a movie star from Adam, you will still be hypnotized by Marclay's canny creation of sequences. He plays around with editing, intercutting scenes from different films to underscore the amazing trickery of the film cut. A character opens a door, he cuts to a different character entering a different room. A character from ancient history asks for the time; cut to the close up of a digital wristwatch. He makes us realize how used we are to this language of cuts that compress time and storytelling. Cinema as shorthand for time.

The sound editing is magnificent. Sound and music foreshadow scenes or leave the trail of a scene behind. For instance, a clip of the final scene of Truffaut's The 400 Blows, shows Antoine Doinel greeting the sea for the first time, but the clip is shown with the music from Jane Campion's The Piano, and then, in a lovely lyrical echo, it cuts to little Anna Paquin doing cartwheels on the beach.

Yet luckily for us, Marclay is not a movie buff. He is not making value judgements on the films he loves, or bragging about his film knowledge. He picks from good movies and bad, but he has a great eye and great timing and rhythm, and picks visually arresting scenes. The clips flow seamlessly, and work exactly like the narrative in a movie, creating emotional landscapes, humor and suspense, a compressed history of human beings in one day. You will find yourself deciding that you are leaving, say at 11, only to find yourself staying to see what is going to happen minutes later. It's about the human need to know what happens next.

There are sequences about death, sex, eating, working, playing, dreaming. So many people fumble in bed trying to turn off the alarm clock, so many people are always jumping out of bed, late for something important they are about to miss. You can clearly grasp the difference between the stillness of bonafide movie stars and actors of a lesser caliber. The Clock makes you conscious, if you are of this persuasion, of every single aspect of the artifice of film: light and shadows (particularly in black and white), the symmetry of the human face, framing, camera movement. You see the artistry of great masters like Polanski in a morning scene where Mia Farrow, in Rosemary's Baby, wakes up to reveal horrible scratches on her back; a marvel of elegance, irony, horror and revelation, in contrast to shoddy pans and careless camera work by lesser craftspeople.

The Clock can be deliciously overwhelming, almost disorientating, for movie obsessives.

On another level, The Clock is a visceral, subconscious experience. After I saw it, I had fabulous dreams about making movies with a cast of thousands. At some point you kind of forget about the movies and you focus on the actions, on the almost hypnotic, mantric quality of the footage with its spirals and repetitions and its relentless flow. You are transported by the sudden realization that you are extremely conscious of the time (you don't need to look at your watch, the movie tells you exactly what time it is), how long has it been since you've been transfixed by the illusion of time in the movies, in which one minute can be an eternity or it can go in a blink. You become extremely aware of time flowing or seeming to stop. Sometimes it is amazing that not even a minute has elapsed, and it seems to be 9 am forever, while sometimes you are caught in the reverie of this flowing continuum, and you realize you've been sitting there for three hours.

It is also a bizarre window into the human experience. A massive, delicious, extended dream sequence enacted by people who look much better than us, because they are the stuff of our deepest dreams.

Jul 22, 2012

Batman: Review Of A Movie I Ain't Gonna See

And it's not because of the massacre in Aurora, but because Christopher Nolan's pointless, bombastic extravaganzas are not my cup of tea.

Yesterday we were trying to find a midnight show at some cineplex in order to avoid the long, slow and totally worth it line to see The Clock at Lincoln Center, and the only thing playing was The Dark Knight Rises. We simply did not feel like being barraged by adolescent inanity camouflaged by grandiosity and humorlessness.

You will be reassured to know a patrol car and two police officers were guarding the theater.

Here is a review by Anthony Lane I sense is close to my own heart.

And here is one by Rex Reed which sums up my feelings about Inception, one of the few movies I have ever walked out of.

Plus, anyone who hides the face of Tom Hardy behind a mask deserves eternal damnation.

Jul 18, 2012

Moonrise Kingdom

Gorgeous. Every frame a marvel to look at. Great style, exquisite taste. Drollness, panache, a sweetly deadpan sense of humor, great visual timing, a flat affect that belies a delicate sensibility, sweet emotion without histrionics; a wash of melancholy and unfulfilled longing for more in life: in short a Wes Anderson movie.

Moonrise Kingdom is a wonderful experience, the story of Sam, a troubled boy (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward), who are in love for the first time and want out of their normal worlds where they are misunderstood. He is an orphan in a foster home where he is unwanted, she is the pouty daughter of two loveless lawyers (the great Bill Murray and Frances McDormand), and they elope, wanting nothing to do with a world with which they are at odds. It's a movie about children trying to grow up to be better adults than the existing ones, into people who can still love and dare and live life without making so many painful compromises. It is also, surprisingly, particularly for an American film, about the blooming of sexuality, about the age where a crush can become a romance and boys and girls become men and women. Anderson treats this theme with honesty and sensitivity, instead of crassness. It is so mature and refreshing, it feels almost European. Moonrise Kingdom is hopeful and sad and the most emotionally rounded and satisfying of his films to date.

It's also lovely fun. His quirky world includes a troop of efficient, much decorated Khaki Scouts, led by scoutmaster Edward Norton, and a storybook house where mom and dad communicate with the children and each other through a bullhorn. The look is a mix of faded color postcards, French films of the Seventies, Fifties style Americana, and that unique Wes Anderson framing which puts people at odd placements in the foreground and stages delightful tableaux vivants or intricate choreographies in the background. He is a great visual satirist and gets many chuckles out of the smallest details in the frame. Anderson's undeniably lovely aesthetic has more than a whiff of the obsessive compulsive, as he crams so much gorgeous detail into each frame. But he is also a gifted choreographer of sequences, and the movie is a mix of frames that almost look like snapshots and extraordinary flourishes of clockwork-like movement. A couple of these sequences take your breath away. A long pan through the scout base camp at the beginning of the film must have been aided by digital stitching, because it seems impossible to pull off in real time, and a wonderful sequence at the Scout Hullaballoo camp where everything is in twirling motion, with completely different things happening in the foreground and in the background - extremely refined visual slapstick. When the plot calls for spectacularly expensive action sequences, he goes whimsical and stages them with props, in a deliberately naive way, which gives the movie a storybook quality.

The cast is indispensable: Bob Balaban as The Narrator, who looks like a garden gnome, Murray, McDormand, Norton, Bruce Willis, playing against type as a sad sack, Tilda Swinton as a brisk entity called Social Services, who looks like a cross between a Salvation Army recruit and a Pan Am stewardess, and in a surprise cameo, Harvey Keitel as the boy scouts' supreme leader, which is surely the best joke in the movie. The two young lead actors seem new to acting and they have a stiffness that conveys the awkwardness of romantic entanglements at their age. They also have the kind of deadpan that perhaps could be difficult to coax from overtrained, hammy child actors. Sam fares better than the Suzy, who, although beautiful in a moody French gamine of the seventies kind of way, is really quite inarticulate in front of the camera. Even if they are the same age, or perhaps she is a little older, she looks like she is about to sprout into a full fledged young woman, while he still looks like a child, which is true at that age in real life. Anderson gets a lot of sweet comedy with his hero's nerdy look and big glasses, but all he can do with Suzy is regard her serious loveliness. It works nicely as a conceit but I had a wee problem: I did not feel that these kids were actually in love. It's a nitpick, because even without chemistry between the two, a sweet strain of romantic melancholy pervades.

Wes Anderson's multiple stylistic flourishes threaten to wear out their welcome, and the film sags a bit in the middle, but to his and fellow screenwriter Roman Coppola's credit, they always add lovely emotional twists that keep the audience enthralled. Moonrise Kingdom feels to me like the most melancholy, intimate and emotional of his films. The balancing act he achieves by combining so much artifice with emotion is very impressive.

As always, the musical score is poignant and exquisite. This time, he enlists the help of Benjamin Britten's "Young Person's Guide To The Orchestra" and "Noye's Fludde", to help convey the themes of how to go about your life step by step, and of the stormy turmoil of love, but the first work also resonates as a musical metaphor for the composition of a film, with all the different instruments/elements/departments coming into place to create a harmonious whole. The rest of the music is by Alexandre Desplat, the scouts' tom tom music is by Mark Mothersbaugh (formerly of Devo), and there are some wonderfully haunting Hank Williams songs as well.

Anderson, whether you like him or not, is a truly contrarian spirit in American films. He is a maverick, in his own quirky way. He has always bucked convention and I applaud him for sticking to his guns and making films with his unmistakable, and not easily replicated style. Actually, the style is ripe for easy imitation, and has been copied to death in commercials. What is not easily replicated is his sensibility, his wondrous command of tone, unsentimental yet moving, magical without being cliched, whimsical without being cloying, light yet substantive, which gently sways between arch, dry, funny, sweet, sad, and haunting.

Jul 16, 2012

Beasts Of The Southern Wild

Watching the preview of this overblown, pointless mythical fantasy, I knew it was not the movie for me, but I was curious to see what the fuss of this much awarded movie was all about. I found it grandiose, illogical, undisciplined, pretentious and borderline offensive.

This much I know: it has to do with polar ice caps melting and flooding the shores of Louisiana via Katrina. It portrays the life of dirt poor (and dirty) inhabitants of a bayou called The Bathtub. It is narrated by a young Black girl called Hushpuppy who, in the first false note of many, talks in voiceover narration like what I imagine young Kierkegaard sounded at his most articulate, around the age of 18. She speaks in "poetry" about the universe and how we are all in this together. She lives with an alcoholic monster of a father who neglects her, but is supposedly trying to teach her to fend for herself. Though Quvenzhané Wallis, the fierce little actress who plays Hushpuppy is the best thing in the movie, she is almost drowned out by the surrounding debris. Her father is revolting. So is pretty much everyone else. These people, black and white, live in utter filth. I don't know if this is the director's idea of poverty, or he thinks he is channeling Beckett, and their unsanitary conditions are a metaphor for something, but if you can't tell, and it distracts you, it's a problem. The tone of this movie is gross and pretentious at the same time. It is a stomach turning mix of clashing tonalities: a deliberately uncouth aesthetic badly blended with poetic effects that never mesh together logically or symbolically.

I have a severe loathing for moneyed, liberal arts educated people who put it upon themselves to fantasize in lieu of the poor by putting their well-meaning, self-absorbed fantasies in the mouths of the poor. How dare they? How can they possibly pretend that they know what the poor dream of? I bet it's not about giant boars and the universe and the planet, and how we are all interconnected. I bet that given a chance, these benighted souls would be happy to decamp at least for a few hours for a warm shower at the nearest Holiday Inn, but in director's Benh Zeitlin's imagination, they are supposed to be heroes for sticking to their mud and behaving in the most self-destructive and irrational of manners. I know that many people refused to leave as Katrina hit, so this is not my beef. It's the way they are portrayed, like pack animals, that I find appalling. This is idealization of poverty by degradation.

The characters are stick figures of abject poverty, and black and white get along like a house on fire (really? in Lousiana?), while they are all in the service of a bombastic allegory about what we are doing to our planet that would be better served by a National Geographic Special. The poetry, with magical realist touches, entails a jerky hand held camera that seems to have delirium tremens, and glimpses of roaming giant wild boar (I guess the beasts of the title) which represent the uncontrollable power of nature.

I am not squeamish, but this movie left a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach, because I sensed a terrifying lack of genuineness and of real humanity. I sensed the revolting pieties of politically correct preoccupations disguised as a fabricated myth, which can never ever in a million years amount to art.

Plus, a ton of other precious bullshit and zero irony.

You know you are in immature, mental masturbation territory when a sequence at the opening of the movie is almost identical to one of those insufferable Levi's "Go Forth" commercials. Tired magic realism clichés abound. One of the neighbors, a kindly black gentleman (of course), wears a bowler hat at all times. Some little girls swim (for no reason I could understand) towards a vessel that delivers them into a softly lit, Fellinesque (they wish) floating brothel, where they are cuddled by kindly whores in nighties. That's when I threw in the towel.

There were three things I liked: The scary sound of the storm pounding on the shack as Hushpuppy and her father brave the storm; an old guy who, passed out from drink, opens the door the next morning and plunges into the flood, and a magical realist moment when Hushpuppy's father recounts how her mother was so beautiful she made the stove turn on and water boil by spontaneous combustion. The rest was hard going.

There have been great films about poverty: Los Olvidados, The Bicycle Thief, Nights Of Cabiria, and many more (curiously, can't think of any recent ones). There have also been films that exploit the poor to make the not so poor feel smug about their own good intentions (Pixote, Slumdog Millionaire and this one). The difference is that the good ones have flesh and bone and heart and soul characters you can recognize as fellow human beings. None of the people in this movie have anything to do with anyone who is alive in this planet, even if the director fished them out of the bayou one by one; and it is not because they are poor and barely literate, but because they have no reason to exist other than to serve his pretentious manifesto.

A very interesting antidote movie to this one, which touches upon similar themes of man and nature, but with grace and beauty is the Mexican film Alamar. It's worth comparing the two. Alamar will feel like a cleansing after this grotesque film.

Jul 12, 2012

Magic Mike

I have a newfound respect for Channing Tatum, hero, producer and inspiration of this uneven film by Steven Soderbergh. He is a charming, confident actor and he can bust a move (who knew?). The story goes that he used to be a male stripper and this film is based on his experiences. Good for him.

He is chiseled to perfection and gorgeous to look at: All-American Beefcake Extraordinaire. He could be the offspring of Tommy Lee Jones. He reminds one of actors like John Wayne, or even Gary Cooper. A real guy. A man's man. Not a hipster wallflower, this one. In my fantasies, I see him as a Marine, or an officer in the Yankee Army, who comes in uniform to sweep me (Scarlett O'Hara with glasses and no Tara) off my feet. American movies today need intelligent, sensitive, sensible beefcake like him. We've had a shortage of his kind for years. He is eminently likable, he has personality, unlike some of the other beefcakes Hollywood tries to foist up on us, such as Taylor Lautner or Taylor Kitsch, good examples of pumped up human nothingness.

Magic Mike belongs to a hallowed category of American working class stiff movies like Urban Cowboy, Saturday Night Fever, and An Officer And A Gentleman. It is no coincidence that Soderbergh uses the Warner Brothers logo from 1972 to 1984, the period when some of the aforementioned movies were made. Like these films, Magic Mike is about what American people have to do to make a decent living. Except in this case, the working class heroes are male strippers in Tampa, Florida. This, of course, is a big exception.

Those expecting something darker, a jaundiced view of American entrepreneurship along the lines of Boogie Nights (working stiffs, no pun intended, in the American porn industry), will find Magic Mike a much more conventional film, a straight-laced morality tale, not about sex, but about work ethic. I'm not sure if it intends to be radical by delivering so conventional a story (feebly written by Reid Carolin), but Magic Mike somehow misses the opportunity to make a stronger statement about a number of interesting themes.

It makes much of the guys' need for money. These are people who earn each and every dollar bill they make. Money comes to them in fistfuls, a dollar or five bucks at a time, depending on pelvic thrust. They happen to live in Florida, world capital of financial hubris. For all the hard work Mike does, (he has more than one job and builds furniture), he lives in a pretty nice house steps away from the beach. Still, he can't get a loan to start the business he is passionate about, which has nothing to do with stripping. His is the story of achievement through honesty and hard work, not easy money and deception.

The other salient topic is the selling of sex, in this case, male to female. There is one scene where the love interest (played by nonentity Cody Horn) watches Mike's routine at the club. Like all of us in the audience (comprised mostly, the night I saw it, of excited young females), she is spellbound by his physical glory, his sexiness and his talent as a stripper (these men work hard to put on a show). There is sexual longing in her gaze, but there is also disgust. How can these guys stoop so low?

We are used to seeing women perform in strip clubs in real life, films, and cable TV, and nobody finds this uncomfortable, even though the female version of stripping is by now almost completely devoid of romance, fantasy or narrative, and it has become mostly hardcore smut. But show dudes pleasing women's libidos by stripping and undulating, and a frisson of discomfort, embarrassment and thoughts of homoeroticism rise to the surface. In real life, how many male stripper clubs exist today in comparison to "gentlemen's clubs"? Must be one in thousands. This is a disparity that goes right to the core of the profound inequality between the sexes. The movie only hints at it by training the camera mostly at the male bodies.

The first scenes of the strippers, both in their dressing room and in their choreographed routines are bracing, exciting, and fun. It is shocking to watch men unabashedly bump and grind at women. The club, as these clubs are, is a safe place for women to let out some steam. It's perfect for bachelorette parties, girls celebrating their passage into legal drinking age, girls' nights out, etc. The stripping dance routines are fueled by fantasy (firemen, detectives, policemen, construction workers, soldiers, doctors, etc), and there is something fun and lighthearted, almost innocent, about the whole scene. Soderbergh spends a lot of time on those male bodies and shows little of the club's clientele's reactions, to the point that the women become just blurry backdrop. I wish there was more of their titillation, their elation and their desire. More of the female gaze.

The movie has no time to dwell on this fascinating topic, preferring to focus on melodrama; the trials and tribulations of Mike, a decent, hardworking, talented guy who likes to make furniture from discarded debris and is wary of relationships. He helps Adam, (Alex Pettyfer), a dropout and slightly shady 19 year-old he meets at the construction site where he works by day, by introducing him to the world of male stripping. They are polar opposites. Mike is hardworking, has principle and straight ambitions, even if he loves threesomes (always with two women: all the strippers in this movie seem to be militantly heterosexual). Adam is blinded by the easy money and the easy sex. Adam's sister, Brooke (Cody Horn) is the ornery love interest who chafes at the thought of her brother and Mike belonging to this crazy circle of strippers. Matthew McConaughey, finally remembering he has always been a solid comic character actor, chews the scenery as Dallas, the flamboyant, fickle owner of the club. Their story is interrupted many times by dance routines at the club. After three or four dance scenes, the routines get boring. They stall the story. At the same time, the earnest, shoddily written story stalls the fun. The result is a movie that feels both long and undercooked, a fact that is not aided by mostly asinine, unimaginative dialogue that seems to have been lifted directly from Mumblecore. Some scenes feel like hack work, others are very effective. A particularly fun scene is when Adam undresses in front of the audience for the first time. The embarrassment, the mettle, and the churlishness he displays by being totally artless are what makes his stripping sexy. And there are a couple of funny moments delivered by good comic timing in editing, particularly involving McConaughey. But I have a feeling that Soderbergh's heart is elsewhere. There is a fuzziness, a lack of focus that feels distant and uncommitted, particularly compared to other, much more polished work from him. Some of the story doesn't make sense, as when Adam clearly betrays Mike and in the next scene they are hanging out as if nothing happened. I also don't believe Mike forgives and helps Adam for love of his sister Brooke. Mike slowly comes to regard Brooke as relationship material, but Cody Horn is so uncharismatic that her presence actually zaps the movie of life. This is the kind of creative decision that turns a decent movie into hack work. Brooke is a big, juicy part that should have gone to a better actress. But Horn happens to be the daughter of Alan Horn, the ex-Warner Brothers studio chief. Maybe she came with the financing. Ah, the things one has to do to make an honest living in America...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)