Dec 29, 2012

This Is 40

...hours long. Which is a real pity, because there is much in Judd Apatow's nepotistic extravaganza that is funny and true. That Apatow can turn the extremely privileged, self-absorbed lives of an LA family (Paul Rudd and the Apatow femmes: wife Leslie Mann and daughters Maude and Iris) into something moderately endearing is a testament to his gifts as a comedy writer. Unfortunately, he could have benefited from more artistic distance. As in, don't cast your own family; you may have more freedom to be disciplined, and perhaps even to dig deeper and make a much more resonant film about family troubles.

This Is Forty is self-indulgent in the benign way in which parents dote on their kids. Apatow is too in love with his family, (even as they are a pain in the ass sometimes, as he makes abundantly clear) to whip the story into shape. There are many pointless scenes, improvisations are messy, potentially interesting themes, like people having second families, are not pursued, and certain plot threads are unconvincing afterthoughts, like the belabored conflict with the grandfathers (Albert Brooks, incapable of playing nice, bless him, and John Lithgow, pitch perfect as a pinched Wasp).

Paul Rudd is his usual game self, as Pete, who apparently did amazingly well at some point in his life, but now he owns an independent music label and is incapable of signing a lucrative act. He seems to have all the money in the world, but he can't make more because he is true to his passion for 80s rock. So he's a bit of a loser, as LA goes. Wife Debbie (Leslie Mann) is freaking out at turning 40, even if she has the body of an 18 year old, and a miraculously creaseless face. The movie is a chronicle of the aches and pains of young middle age among the wealthy in L.A., where there is downright hostility against gluten, western medicine and body fat.

Leslie Mann, although giving it her all, is not the most endearing presence to carry a movie. She is best when she is happy, and quite hard to take when she is whiny and controlling, which is for most of the movie. Although playing as loosely as they can, she and Rudd seem uncomfortable around each other. The movie's rambling self-regard ends up exhausting our good will. This is a more than two-hour long nag.

The movie is mostly good natured, peppered with some classic Apatovian juvenile raunchiness (on the part of the adults, of course), but I was struck by how it became meaner as it progressed. Pete's dad was incredibly unsympathetic. He is very nice to his daughter in law, but a total dick to his son. Not only is he a relentless, unrepentant mooch, but there is a scene where he is also a coward. A scene in which Pete and Debbie lie through their teeth is funny, but it undermines our rooting for them. There is nothing wrong with people behaving like dicks in comedy, but the tone of this movie wavers between the adoring and the disparaging without ever achieving balance.

Dec 27, 2012

It's The Makeup, Stupid

Here are some of my thoughts on why it is very possible that Daniel Day Lewis will be nominated for an Oscar for Lincoln, whereas Anthony Hopkins, also delivering a flawless performance in Hitchcock, may not.

Enjoy!

Dec 26, 2012

Life Of Pi

I was very skeptical about Life Of Pi, which, with a combination of 3D, computer effects and the threat of syrupy spirituality, was as appealing to me as a date with the Holy Inquisition. Having not read the book by Yann Martel, I expected the worst. I hate spirituality. I don't have it and I don't like it when people rub it in, especially in entertainment.

Well, I'm happy to report that this lovely, thoughtful film by the ever elegant Ang Lee is very beautiful and enjoyable. Life Of Pi turns out to be a parable of the myths and stories we need to imagine in order to endure the human condition, the cruelty of nature, the vagaries of fate. At the beginning, I was confused by the opening credits. I couldn't tell what was shot in real life and what was computer animation. If this is disorienting at first, soon it settles into a spectacular mix of both. The film is so gorgeous, so luminous, that before Pi endures his shipwreck, it feels like the most pleasant, gentle meditation, a gift for the eyes. Lee sustains an unhurried, yet never boring, pace as the older Pi (the always welcome Irrfan Khan), tells his unbelievable story as a flashback to a young writer (Rafe Spall, soulful). Pi is a gifted, curious child, an outsider with an eccentric name other kids make fun of. In Pondicherry, where he grows up the son of a zookeeper, he is in familiar terms with the wondrous stories of the millions of Hindu gods, but he also likes Jesus and he also likes Islam. The young Pi instinctively understands all these religions as different versions of one God he believes in. His father, a rational man, cautions him against the darkness of religion. He tells him he doesn't mind Pi believing, but he needs to use reason to arrive there. So far, so good.

Soon the poor Pi, now a young man, is stuck in a lifeboat with Richard Parker, a fearsome and beautiful Bengal tiger. God is nowhere to be found and nature takes over. Pi is a vegetarian and a protector of animals. But from a former encounter with the tiger when he was a child, he knows that Richard Parker will tear him to pieces, so he is stuck trying to manage the beast as they float on the vast ocean, all alone. I braced for new age pieties and corny clichés, or for Disneyfied animals who suddenly decide to become "man's best friends" and crack jokes; thankfully, they never showed up. They are animals and they behave as such. Pi (Suraj Sharma, a great sport) is intelligent and resourceful and learns how to survive inclement nature. Nature is shown to be as beautiful and generous as it can be ruthless, and as magnificent as the images of the different moods of the ocean are, nature's behavior is never a sanitized fantasy. The scenes of a cargo ship capsizing in a violent storm are very powerful. In general it is pretty astounding how Lee manages to never stray from an intellectually honest journey, with a credible hero, in the most fantastic of circumstances. He never gives in to sappiness, or to out of control special effects. The sensibility of this film is not what is usually found in American 3D blockbusters. That is to say, this is a movie about complex themes, where people, animals and nature all behave credibly. It does not condescend to the audience. The 3D is used elegantly and in harmony with the story, there are no cheap thrills. Chapeau to Ang Lee for never succumbing to the easy and obvious: it is an amazing directorial feat. He combines a subtle, sensitive touch with the certain control of a dictator. Only a dictator could whip the complexities of shooting with such technology for what is essentially a delicate story, into a coherent, meaningful, artful shape.

There is a wonderful philosophical twist at the end that will leave atheists and believers equally happy. Agnostics will interpret this parable as saying that God and religion are yet another necessary human story. Those who believe will see the hand of God in Pi's deliverance.

Dec 24, 2012

Zero Dark Thirty

The Hurt Locker is a much better movie. So is Paul Greengrass's United 93, the greatest film ever made about 9/11. It's worth comparing it to Zero Dark Thirty, because Greengrass avoids every single pitfall that makes Zero Dark Thirty a problematic entertainment. For one, he uses no recognizable movie stars; glamorous faces do not remind us that this is only a movie and egregious liberties have been taken with the story. He also eschews the conventional single hero narrative for a fragmented "you are there" style, which shows massive government incompetence, as well as moments of individual courage. Perhaps because he is not American, he was able to sidestep the trite, incurable hero syndrome that seems mandatory in every Hollywood movie. Hence, United 93 honors history by rendering it as faithfully, realistically and intimately as possible. Its impact is devastating. True, nobody saw it, having no stars and dealing head on with a terribly painful collective moment; whereas Zero Dark Thirty will be much more commercially successful. One, because it is about triumph, not loss; and two, precisely because of its lack of authenticity. Even The Hurt Locker, a great American anti-war film, has more conviction and more outrage than ZDT.

My first problem with ZDT, and a cardinal sin in film, is that I was bored for a very long time before things got interesting, which only happens in the last third of the film, when they finally move to capture Bin Laden. ZDT seems to take as long as it took the US to nail Bin Laden. I wouldn't mind the procedural if it were riveting, but it isn't. It is plodding. Scene after scene dutifully documents the torture techniques utilized by the US in the war against terror. It's a deeply uncomfortable laundry list: conveniently outside of the purview of our laws, CIA agents use waterboarding, torture prisoners with sleep deprivation and hardcore heavy metal, stuff them in tiny boxes, hang them for hours, humiliate them with dog collars, and play mind games. The main torturer, played by Jason Clarke as if he was warming up for his daily tennis match, is deliberately made to be a very casual American dude who refers to his victims as "bro". I applaud the fact that we are not in for mustache twirling villains, but where is the bete noire in his soul? Are the filmmakers saying everyone can become a torturer if the justifications are strong enough?

Critics are hailing ZDT's obfuscations as moral ambiguity. I beg to differ. The movie is afraid of its own point of view, which is actually unclear. Critics are celebrating the mere fact that ZDT dares portray the issue of American torture (as if we didn't know plenty about it already), but the problem lies in how it is portrayed. I do not think that the movie glorifies torture, but I'm not sure that it condemns it. In the end, it isn't clear whether the film infers that torture helped get information that led to Bin Laden's capture or not. This is a problem. Granted, it would have been revolting to have Maya, the CIA agent heroine (Jessica Chastain, miscast), give epic speeches about the evils of torture, the kind of wishful fairy dust that Hollywood sprinkles around in its issue movies to feel better about itself. Alas, the script is content to show her silent discomfort as she attends some of the torture sessions, yet not much later in the film she daintily prods a torturer to slap a detainee. We never see how she really feels about this. Is she just following orders? Does she think the means justify the ends? It would have been interesting if we saw her take a stand, any stand. But ZDT is as wishy washy about the torture issue as the central character. And herein lies the problem: this is a contrived entertainment that takes something that happened in reality and makes it into a formula with a single heroine, therefore stripping it of any legitimacy or authenticity. It doesn't want to be Rambo, but it doesn't have the guts to go the other way. It seems as if director Kathryn Bigelow and writer/producer Mark Boal are torn between presenting a realistic portrayal of the hunt for Bin Laden, or crafting a conventional movie narrative. Had they chosen the first option, Zero Dark Thirty could have been a much stronger film. But the decision to center the story in a single heroine dooms the movie. Big deal if she is a woman. She is utterly boring as a character, just a reminder that this is a fantasy fiction based in reality, and not a film which really aims to explore the complexity of this war.

Except for the fact that she is an obsessive workaholic without a life (bo-ring), we don't really know who CIA agent Maya is. It is said by other characters that she is a killer, How do we know this? She works long hours, stares a lot at screens, and is a pest to her superiors. I did not believe her character for a second. Not because she is a woman, but because, in operations like this, it is ludicrous to pretend that ONE relentless person, dead set against everyone in the CIA and the rest of the world, was responsible for the capture of that maniac. It's just immature. And don't get me started on the final frame, of her sitting by herself on a big ass military plane, crying. What is this supposed to mean? America is sad for all the torture?

The best parts of ZDT are the actual action sequences towards the capture of Bin Laden, precisely executed both by Bigelow and by the guys who play the commandos that got it done. As in The Hurt Locker, Bigelow is good at relying how soldiers actually communicate in the middle of an operation. Minimal words, all instructions. The way bombings occur, without warning, as it is in real life, is jolting. Boal and Bigelow do everything in their power to show decorum and restrain at the storming of Bin Laden's compound. Everything else reeks of fakeness. Cringeworthy plot devices creep in: it is not enough to want to capture the barbaric mastermind who engineered the loss of thousands of innocent people all over the world. As this is a movie, Maya has to have a personal reason to vow to nail Bin Laden. This turns out to be the death of some of her CIA colleagues in the car bombing of a US base in Afghanistan. Puhleeze. Albeit suspenseful, this sequence is so telegraphed, so movie-like, that one thinks that if CIA agents are stupid enough to let a car breach inspection into an American military base in that hellish part of the world, they deserve what they got coming.

Meanwhile, the filmmakers have Maya, this supposed "killer" agent, sit obediently in the back at all important meetings as the boys make plans, and then when she opens her mouth, she says a one liner that strains credulity. For a "killer" agent, she behaves like a schoolgirl, petulantly scribbling in her bosses' window the number of days that go by without capturing Bin Laden. Puhleeze.

Then there are bizarre casting choices. Were American actors afraid to make this movie? The main torturer is played by Jason Clarke with a clear Australian accent. I spent half the movie trying to figure out if Australians were farmed out by the CIA to do our torture for us. My current boyfriend, Mark Strong, does an impeccable American accent, as does Joel Edgerton (another Aussie). But why cast a British actor, Stephen Dillane, as an American national security advisor? He sounds like he's ready for tea and crumpets. This is the CIA we are talking about. Everyone needs to sound like John Wayne. As for Jessica Chastain, she tries her best but is a movie star, and hence completely wrong for the role, for this and other reasons. Remember, very few people had seen Jeremy Renner when he starred in The Hurt Locker.This makes a huge difference: better movie = less box office. In an ideal, ageless world, someone like Frances McDormand or Annette Bening would play Maya. Someone with ovaries of titanium. Someone who can look you in the eye and make you unravel. Alas.

It is well known that the filmmakers had access to some people in the government. This seems to have fettered their imagination. This movie is more interesting for all the stuff it leaves out. Was it ever discussed if Bin Laden should be captured alive and brought to trial or was it, as the movie shows, a fait accompli to get him killed? I would have loved to see this conundrum dramatized. The CIA agents in the movie don't seem to have an opinion, pro or against, of what their superiors are asking them to do. There is no conflict, no dialectic, they are just executors. This is extremely problematic, as in foot soldiers that commit atrocities and chalk them up to just following orders.

Hence, I find it rather revolting that some critics have decided to bestow a Best Film of the Year award upon this confused movie, which leaves out all sort of interesting questions in favor of an impoverished, oversimplified narrative. I find it rather repulsive for a movie to be awarded accolades just for owning up to America's unsavory policies without having the balls to have a point of view about them, either for or against. It is also pathetic to overpraise a movie just because it deals with a difficult topic in a way that isn't Rambo. This sets a very low bar.

Dec 22, 2012

The Impossible

The only authentic part of this movie by J.A Bayona (The Orphanage) is the spectacular, utterly realistic recreation of the tsunami that hit Southeast Asia in 2006. The special effects are truly extraordinary, but the movie, sadly, is not. All the attention of the filmmakers seems to have gone into the creation of the special effects at the expense of character, or arc, or anything resembling a fully realized story. It has a very weak script. Mind you, I cried like a banshee at the sight of blatantly manipulative human emotion under extreme duress; beautifully enacted by all the amazing blonde and English speaking actors who portray the Spanish family upon whose real story the film is based.

Naomi Watts, Ewan McGregor and the three outstanding young actors who play their kids, deliver real emotion in spades. If it weren't for them, the movie would be dangerously close to a dud.

The problem is that the filmmakers have decided to abandon authenticity for the promise of global box office success. I'm not sure the bet will pay off, at least here in the States. The screening I saw yesterday night (Friday opening) was almost empty.

Now, The Impossible is a full-fledged Spanish production: from director J.A Bayona (The Orphanage), to most of the film crew and armies of special effects and hair and make up people (unbelievably awesome job). But instead of, say, using megastars Javier Bardem and Penélope Cruz and three Spanish boys to portray the family, speaking in Spanish with subtitles, or even in heavily accented English, the producers thought that they could gain a wider audience by making everybody blond and English. It's a waste of energy to decry the plague of unfair casting practices in commercial movies. It is unfortunate, but part of the reality of film today, which is that films need stars to get made and seen, and stars, for the most part, tend to be white. The irony here, not to detract from the soulful and generous work of Watts and McGregor, is that they are not bigger stars than Bardem and Cruz, who are a galaxy unto themselves. So this Anglo casting does not necessarily guarantee a wider audience. The plot is feeble. It follows the fate of Maria, the mother, played by Watts, and her oldest son, Lucas. It strands the dad and the other two kids offscreen for two thirds of the film. This is a huge missed opportunity to show more effects and to explain to the audience what happened to them without resorting to exposition. This is a rare instance where I wish that some Hollywood hand with a knack for disaster could come to the rescue, because even as there is a tsunami aftermath going on, not much really happens. The script does not seem to know or care about who is this English family living in Japan, what makes them tick. I bet had they remained Spanish, the filmmakers would have naturally understood who they were and the story would be much richer.

Bayona, bereft of a good plot, manufactures cheap, vapid emotional cliffhangers. He is adept at creating a sense of menace, as he showed in The Orphanage, a film that scared the living daylights out of me. In the first minutes of The Impossible, before the tsunami hits, he shows the tranquil ocean and the colorful little fishies swimming in it, and we get a tingle of dread, bracing for the unimaginable devastation that is soon to come. And he dares to imagine it, brilliantly. The way in which he portrays the feeling of getting swept and mangled by a giant wave is extraordinary. But any time the characters open their mouths, out come the most inane lines. The movie works best when no one speaks. And, not trusting that the audience's emotion flows naturally from following the family's terrible upheaval, he contrives scene after scene of unnecessary audience manipulation, without the grace or skill of a blockbuster master like Steven Spielberg. Overwrought orchestral music does not help. Too much repetition blunts the impact of sweeping crane shots of the devastation. Worse, towards the end of the movie, Bayona repeats the scenes of the tsunami. At the beginning, I marveled at the skill and restraint he showed on keeping them short for added realism and power. Seeing them once is enough for them to leave an indelible impression. Showing them twice is a huge miscalculation.

My theory is that the Spanish government financed this movie in the hopes of bringing some SFX industry to its shores, like Europe gives Woody Allen money each year to film tourist brochures of its most charming cities. If I were a Hollywood mogul, after seeing what the Spanish can do with special effects, I'd scream "get me Madrid! But there is a crass whiff of calculation in making everything (except the tsunami) as generic as possible, missing rich opportunities to explore how privileged tourists and poor locals were affected, came together, or were torn apart by their inequities. When the only villains in the movie are an American couple who won't part with their cellphone, it is gratuitous and idiotic. So much could have been mined. Instead, we are left with the musty poverty of "the power of the human spirit", as boring a cliché as any.

Dec 18, 2012

2012 Best and Worst And Everything In Between

This was a good year for movies. These are films I saw during 2012. As I recall them, some of them have made an indelible impression while others, even as I loved them coming out of the theater, fizzle out in memory. Some gain in estimation, while the hatred I have for the ones at the bottom of the barrel has not abated.

Some of the following films have not been released yet. I am missing several major ones, opening this week and next, which will be added in the coming days.

Extraordinary

Amour. Michael Haneke

Rust And Bone. Jacques Audiard

Caesar Must Die. Vittorio and Paolo

Taviani

Beyond The Hills. Cristi Mungiu

Like Someone In Love. Abbas Kiarostami

The Gatekeepers. Dror Moreh

Very

Good

Robot And Frank. Jake Schreier

Celeste And Jesse Forever. Lee Toland Krieger

The Queen Of Versailles. Lauren Greenfield

Ai Wei Wei: Never Sorry. Alison Klayman

Polisse.

Maïwenn

Headhunters. Morten Tyldum

Monsieur Lazhar. Phillipe Falardeau

Tabu. Miguel Gomes

Good

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg

No. Pablo Larraín

Hitchcock. Sacha GervasiSilver Linings Playbook. David O. Russell

Moonrise Kingdom. Wes Anderson

Frances Ha. Noah Baumbach

The Bay. Barry Levinson.

The Cabin In The Woods. Drew Goddard

Fill The Void. Rama Burshtein

A Late Quartet. Yaron Zilberman

The Dictator. Sacha Baron Cohen

Wanderlust. David Wain

The Woman In Black. James Watkins

Skyfall. Sam Mendes

Barbara. Christian Petzold

Our Children. Joachim Lafosse

Wanderlust. David Wain

The Woman In Black. James Watkins

Skyfall. Sam Mendes

Barbara. Christian Petzold

Our Children. Joachim Lafosse

Good but Flawed

The Master. Paul Thomas Anderson

The Deep Blue Sea. Terence Davies

Bachelorette. Leslye Headland

How To Survive A Plague. David France

More Flawed Than Good

Zero Dark Thirty. Kathryn Bigelow

This is 40. Judd Apatow

This Must Be The Place. Paolo Sorrentino

How To Survive A Plague. David France

More Flawed Than Good

Zero Dark Thirty. Kathryn Bigelow

This is 40. Judd Apatow

This Must Be The Place. Paolo Sorrentino

Annoying

We Have A Pope. Gianni Moretti

Magic Mike. Steven Soderbergh

Dark Horse. Todd Solondz

Something in The Air. Olivier Assayas

The Impossible. J.A. Bayona

Cloud Atlas. The Wachowskis, Tom Twyker

Goodbye, First Love. Mia Hansen Love

Take This Waltz. Sarah Polley

The Impossible. J.A. Bayona

Cloud Atlas. The Wachowskis, Tom Twyker

Goodbye, First Love. Mia Hansen Love

Arbitrage. Nicholas Jarecki

The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. John Madden Take This Waltz. Sarah Polley

Killing Them Softly. Andrew Dominik

The Pits

The Pits

Beasts of The Southern Wild. Benh Zeitlin

You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet. Alain Resnais

Labels:

Ai Wei Wei,

Audiard,

Baumbach,

Cronenberg,

David O. Russell,

Documentary,

Female Filmmakers,

Haneke,

Kiarostami,

Lanthimos,

Mungiu,

PT Anderson,

Resnais,

Sorrentino,

Taviani Brothers

Dec 17, 2012

Out and About

Yours truly is happy to collaborate with Out.com writing about, what else, Movies!

Here's my first dispatch about 5 great movies you may have missed this year and five more coming down the pike. I am happy to report, my post, which appeared today, is no. 6 in the most popular list! Enjoy!

Dec 8, 2012

The Sessions

Based on the real story of poet Mark O'Brien, The Sessions is about the romance between O'Brien (John Hawkes), who lived encased in an iron lung, and Cheryl, his sex surrogate therapist, (Helen Hunt).

It is an intriguing story. O'Brien was 39 years old and had never experienced sex with someone, so he wanted to give it a try. He ends up under the care of very professional, empathetic Cheryl, who struggles to keep the relationship at a distance, but caves under Mark's sweet charms.

The Sessions is gently funny and touching, but there is something too beatific and unconvincing about it; it's not messy enough. The humor befits a sitcom, but the situation deserves more depth; and the treatment of sex, while surprisingly frank for an American film, is like reading an operations manual.

Hunt and Hawkes bring enormous dignity and humanity to their roles and they elevate the movie far above its feel-good script. I wish the movie was not so eager to please the audience. Its sexual frankness is startling for an American film, but it belies a curious lack of eroticism. There is nothing sexy about it. This is not to say that one expects a horny movie with a disabled man at its center. But if Mark's most fervent wish is to experience sex, at the very least there should be some sexiness in his desire, even if he is in an iron lung. If anything, The Sessions is duly tasteful, mostly cheerful, and rather literal. Like its name, it is oddly clinical, and uses humor to deflect from the real nakedness of its themes. The only one who brings an edge to the table is Helen Hunt, very affecting as a woman whose carefully constructed fortress of professional demeanor (in the most intimate of professions) totally dissembles as she allows herself to fall for her client.

I suspect the movie is uncomfortable with its own sexuality. Whereas Cheryl is shown in all her full frontal glory (Hunt looks beautiful), a scene in which Cheryl shows Mark his body through a mirror, is decorously framed above the groin. Well, this defeats the purpose. If the point is to celebrate the miracle of the body, of Mark's body, why not show it as well? To avoid an NC-17 rating? We are still cloistered in puritanical territory, no matter how many times the words penis, vagina, nipples and total penetration are mentioned. One of the wasted themes in this film is the miracle of sexual pleasure, considering, as the movie shows at length, that if you break it down, a lot of stuff has to happen in order for sex to succeed. And while The Sessions is more confident and convincing in the way it depicts love, it is clumsy around sex. Everything is too explicit, in a Masters and Johnson kind of way. What it has in empathy, it lacks in imagination, which is an essential component of eroticism. I can't help but think of Jacques Audiard's Rust and Bone, which is also about an unlikely love affair between a disabled woman and an emotionally crippled man. The sexual tension is there, the desire is there, and that edgy, risky feeling of opposites attracting is powerfully visceral. None of this happens in The Sessions. For all the explicitness and the female nudity, it is still couched in an insipid aura of cuteness, which the two stars, and particularly Hunt, work with all their might to dispel.

Dec 1, 2012

Hitchcock

Or a sunny fairy tale about the genesis of Psycho, of all things. This enjoyable morsel by Sacha Gervasi (ANVIL! The Story of Anvil), improbably turns the story of how one of the greatest artists in the history of film made of one of the scariest movies of all time into a sweet little fable with a happy ending. If it wasn't for the two gigantic actors who portray Alfred Hitchcock and his wife, Alma Reville, it could have bordered on the ludicrous. But it is a joy to watch Anthony Hopkins and Helen Mirren deliver the goods, separately and as a long lasting couple. Hopkins doesn't look anything like Hitchcock, and his cumbersome make up still doesn't make him look anything like Hitchcock, except for the girth. But his characterization is dead on. He is as hilarious as Hitchcock was in his eccentric "master of suspense" persona. For Alfred Hitchcock was a brand. He was as much of a genius in the creation of his own marketing as he was as a film director. Hopkins delivers the quicksilver wit, with extensive pauses between words and a full beat before striking the punch line, just like the original. He is a hoot. His Hitchcock is at once grand caricature and something smaller, more vulnerable, more complicated. A very controlling man, a huge child with enormous, but being British, equally repressed appetites (which explain the rounded figure), a famous director who found himself wielding enormous power, particularly over his female actresses. I don't know if its a trick of camera and makeup or if it is Anthony Hopkins who achieves a chilling distance in his gaze, but this aloofness, this feeling that Hitchcock was always an alien in Hollywood, makes the portrayal rise above caricature.

There is a lot that could be really hokey in the movie, like the sequences where Hitchcock imagines conversations with Ed Gein (Michael Wincott), the real life serial killer on whom the book "Psycho" was based. But Gervasi sustains a lighthearted tone, immeasurably helped by pretty solid casting. He gingerly mentions the dark aspects of Hitchcock's personality without really investigating them, but they are there, more as discomfiting quirks than as truly sinister traits: Hitchcock's obsession with his actresses (the mistreatment of Tippi Hedren in The Birds was yet to come); his emotional blackmail of Vera Miles (Jessica Biel); the way he supposedly got Janet Leigh (a good Scarlett Johansson) to scream her heart out in the legendary shower scene.

But the movie also belongs to the unsung hero in Hitchcock's life, Alma, his wife and creative collaborator, who apparently was in no small part responsible for some of her husband's most brilliant artistic choices, like insisting on using Bernard Herrmann's score over the shower scene, or suggesting he kill off the leading lady before page 30, a first in the history of film. Always toiling in the shadows, but a known secret inside the industry, Alma was a woman of her time, making herself and her talents disappear in favor of the big man. We are reminded that she was once his boss; by this stage, they had been making movies for about 40 years. They were old fashioned in their mores, yet adventurous and visionary as artists. There is a very poignant turn in Alma's story as she is seduced by a colleague (Danny Huston), only to discover that, like Hitch, he is only using her for her brilliance. Mirren then has a controlled, beautiful meltdown where she finally reads Hitch the riot act that almost elicited cheers from the audience. It is a beautiful speech, writerly wishful thinking, and she nails it with such force, grace and skill, it's a cri de coeur for all unsung females who support and even improve their partners' celebrated achievements, with little recognition. Or for all those average, yet valuable women who are eclipsed by more gorgeous ones.

Hitchcock is also, and most enjoyably, about making an independent movie. A famed director, at the peak of his career, finds himself trying to get a movie made that no one will touch with a ten foot pole. Even Hitchcock, who was at the time the most famous film director in the world, could not get financing for what was seen as schlocky material, anathema to casting megawatt stars like a Cary Grant or a Grace Kelly.

At the peak of his career, fascinated by the horrid Ed Gein story, Hitchcock decided to make a B-movie, with second tier stars, for a very low budget, which he financed himself. This was the genesis of Psycho, one of the most revolutionary films of all time. In the few scenes involving Ed Gein and his sleazy serial killer grotesquerie, it implies the genius of Hitchcock in turning a seedy story into an elegant, black and white masterpiece of horror. I wish this film explored more what made Hitchcock a great artist. I applaud that it gives Alma Reville her due, but it cheats Hitchcock of his own genius. We never really see him exercise the elegance of his creative thought, or his masterful craftsmanship.

I can't decide if Gervasi's lighthearted choice is cool or ridiculous, but it is great fun. Hitchcock is a triumphant comedy about a persevering artist, and a lot of the joy in it comes from relishing in hindsight the happy outcome of the story. We are all thrilled by Psycho, by the fact that Bernard Herrmann's music and that shower scene are now universal icons, by how Alfred Hitchcock, a prolific artist, continued making fresh masterpieces in his old age (The Birds, Frenzy), almost as if Psycho had given him a second wind.

Nov 24, 2012

Silver Linings Playbook

The Fighter for laughs. Somehow, David O. Russell takes the tritest romantic comedy tropes and with a game cast, makes a rousing movie that is as enjoyable as it is farfecthed. He likes to mill around regular folks, and make them larger than life, in this case, average middle class people from Philadelphia. The Solitanos are a dysfunctional family, trying to cope with their son and major fuck up, Pat, a manic bipolar man, (Bradley Cooper), recently sprung by his mother from a mental institution. Pat wants to rekindle the love with his wife, who has a restraining order against him. While in the hospital, he has drank the kool-aid of unbridled positivity (never a good thing) and now can´t bear anything short of happy and miraculous happening, even in books. He is committed to getting his wife back, though everybody knows no such thing is going to happen. This is an edgy comedy about people with real problems and for the most part Russell sustains a bristly, realistic tone, investing equally in Pat´s manic suffering as in the painful comedy that results from it. Some of it is a little strained, but there is real heartbreak, and fantastic performances from Robert De Niro and Jacki Weaver as the exhausted and overwhelmed parents of this chaotic grown man. They both seem to have been living with this curse for decades.

If there is someone who carries the movie, however, it is Jennifer Lawrence as Tiffany, a fellow mentally unstable comrade in arms. She is extraordinary as a fierce, uncontrollable woman who is mourning the death of her husband and hitches on to Pat for emotional sparring and support. Even as the plot cliches start piling up, Russell sustains a taut, prickly tightrope between the borderline tragic and the funny. By the time the third act arrives, however, he seems to say "fuck reality" and goes for obvious cliche with all his might. To his credit, it feels less ridiculous than liberating, as if he were overjoyed to embrace everything that is unreal about Hollywood´s happy endings. The more you think about this movie, the more strained the plot reveals itself to be, and in less shrewd hands it could have been a painful groaner. But Russell brings out fierce, beautiful performances from everybody, even Cooper, who gives it his all. Russell keeps us rooting for the bunch of losers he has so much sympathy for. And this is why the movie works somehow.

Nov 18, 2012

Anna Karenina

Shocker: they omit one of the greatest opening sentences in the history of world literature. It's such a great line that it could have been included as a quote, before the story starts. I missed it.

At first it seems that we are in some sort of misbegotten musical, which is not what one expects to happen in any retelling of this tragic story, unless it's an opera. Joe Wright's version of Anna Karenina takes place in the physical realm of a stage. At first this conceit feels labored, distracting and inappropriate, and I was groaning with exasperation for the first 20 minutes, but once you get past all the whimsical dancing, and once this movie focuses in the great story it has to tell, it becomes quite ravishing, if not completely convincing. Screenwriter Tom Stoppard has adapted Tolstoy with verve and several great one-liners. The photography by Seamus McGarvey, the production design by Sarah Greenwood and the costumes by Jacqueline Durran are absolutely stunning, and a good reason to sit through this movie. I hated the vulgar music by Dario Marianelli, but somehow the story of this woman (Keira Knightley) is so good, and the movie is so gorgeous, that one settles into its idiosyncracies and gets carried away, that is, when one is not grimacing at some of its more salient flaws.

For starters, La Knightley is somehow fascinating to watch, although she is not much of an actress. Sometimes she is beautiful; sometimes, as when she laughs, she is not, but she holds the screen, if not with talent, with her looks and her esprit de corps. She carries herself well in costume dramas. As an actress, she is passable in that she does what the character needs to do (cry, swoon, elate), but there is no internal compass. She is just a collection of scenes. Jude Law fares much better as an understated Karenin, whom he plays as a cold, solemn bureaucrat who nevertheless is deeply hurt by his wife, whom he loves in his own prim and distant way. But the biggest problem is the casting of Count Vronksy (I was pining for Fassbender, even if he is long in the tooth). In order for Karenina's amour fou to take root, one has to believe that there is something really fetching in Vronsky, and Aaron Taylor-Johnson is not that interesting. I understand that part of the tragedy is that Vronsky is not that remarkable a man to make such terrible sacrifices for, but he should have a modicum of charisma. Taylor-Johnson is a cipher.

The main problem with this version is that it is too busy hitting the audience over the head about the theatrical rigidity of Russian social mores with the stage metaphor, (which gets old five minutes into the movie), and this takes time and space from character development. We can fill in the blanks about the characters lives', but the characters would have benefited from more attention from Joe Wright. The stage conceit serves as a shorthand to condense the different social milieus of the film without having to turn it into a miniseries. If one fears being stuck with Anna Karenina on a stage (a la Dogville), Joe Wright's swooping camera and flawless transitions between scenes allow him to keep the eye entertained, and sometimes even astonished. Technically, the movie is spectacular. It is also too long, like the book. Many times, the slow pace has to do with Wright getting carried away with the visual spectacle. At the beginning, the forced choreography seems to border on kitsch, but soon they kind of forget about it and get on with the story. The whole movie looks like a Fabergé egg, yet the most enjoyable parts are when the characters are allowed to be, and speak Tolstoy by way of Stoppard's lines. The character actors are uniformly great, (in particular Emily Watson, Matthew Macfayden and Alicia Vikander) and so it's a pity that the two tragic lovers at the center of the story are not at that level. Still, this Anna Karenina is worth seeing for sheer visual pleasure, and to revisit a great story which is more modern than this ornate version wishes it to be.

Nov 12, 2012

Lincoln

Watching Steven Spielberg's film about Abraham Lincoln's political maneuverings to pass the amendment to abolish slavery, I was struck mostly by the sly and open resonance with our current times that screenwriter Tony Kushner achieves as he portrays this specific episode in Lincoln's life.

The movie opens to scenes of Civil War carnage. Steven Spielberg stages a writhing field of brutal violence where Americans fight against each other not only with firearms and blades but with their bare hands. 600,000 Americans died in this bloody conflict, which was, ultimately, about the moral essence of the country. One cannot help but ponder, whether in our day and age, now that the ideological differences of the two main political parties stand in greater contrast than they ever have (even if their allegiance to corporate interests is basically the same), if we will not reach a stage in which we may go literally to war over the kind of country we are meant to be. I personally am rooting for New York City to secede, and to hell with the red states. There is no small irony in the fact that Abraham Lincoln belongs to the Republican party and that the Democrats are the villains in this story. We should thank providence for TV and the internet, which keep enough of us numbed and misinformed, and mostly disinclined to violently eliminate the other side, even as they help raise the cacophony of mutual incomprehension.

Lincoln is a rich, intelligent history lesson on how change is achieved through politics, how compromises and negotiation are necessary in order to make giant strides. Kushner gives President Lincoln a free pass in trying to buy congressmen off in order to pass his amendment. By any means necessary is nice and even humorous when the end is lofty, but I'm afraid that's not how it works the other way around. This resonance applies to Barack Obama and the way in which he has tried, with various degrees of middling success, to make some changes himself. Obama is no Lincoln. No one is. My sense is that Kushner is instructing him to take a lead from Lincoln's playbook and slyly, whether by moving oratory or skillful maneuvering, enact the reforms that need to get enacted.

Spielberg directs the very wordy, literate material with his customary emotional force and splashes of comic relief; some of it a tad broad, if welcome. He frames Kushner's barrage of language with elegance and restraint, and keeps it moving along, slowly but surely. In this he is aided by an enormous performance by Daniel Day Lewis, who at this point is alone in his niche of playing greater than life characters by making them greater than life. To become Abraham Lincoln (he looks uncannily like him), he brings out his entire arsenal of acting wherewithal. The lumbering gait, the schlumpy clothes, a high pitched voice with a hypnotic musical cadence and what I imagine is a perfect Midwestern accent of the times. But as he fusses over the technical aspects, Day Lewis also provides a lively, sexy intelligence and emotional power in the soul of the character. His Lincoln likes to tell stories, has a folksy sense of humor, which he deploys to disarm, quotes easily from Shakespeare, thinks like a lawyer, is a good listener, asks people questions, and is warm and open, yet distant and inscrutable at the same time. Day Lewis is utterly convincing, compelling, and heroic. Thanks to this performance millions of people will develop a huge crush on Abraham Lincoln. He brings to pulsing life what nobody is ever going to bother reading in a wikipedia entry, much less in a history book. If I have one qualm, is that I would have liked to see something less avuncular, more flinty about him, but it is a towering achievement.

The cast is superb. Tommy Lee Jones kills as Thaddeus Stevens, the formidable anti-slavery advocate. He has some great lines to utter and he does it with precision and relish (I predict supporting actor Oscar nom). Sally Field is great as Mary Lincoln. I know people like her. She's a depressive, intelligent, intense woman with not a small chip on her shoulder at having to sit on the sidelines of history. Who is not happy to see James Spader, John Hawkes, Lee Pace, Tim Blake Nelson, Jackie Earle Haley, Jared Harris, Michael Stuhlbarg, and a bunch of other whiskered, wonderful character actors nail their roles? Women too: Gloria Reuben, Julie White, Elizabeth Marvel, S. Epatha Merkerson). It's a character actor dream cast.

Spielberg only veers into the maudlin fitfully. Soldiers reciting the Gettysburg Address to President Lincoln seems a bit ham handed at the beginning, but then the movie thankfully settles into political strategizing. The epic music by John Williams stirs the feelings of righteousness in the audience, but it's a bit too obvious in moments of levity. There is strained, unconvincing business about father and sons. Lincoln's young son is mostly there as a symbolic presence. His older son, played by Joseph Gordon Levitt, insists on going to war, even as he is confronted, in a wonderfully staged scene, with a cartload of severed limbs. In this instance, the political seems far more interesting than the personal.

The movie builds very slowly with rich and copious detail, painting a panorama of the historical moment, but by the time the vote comes to be passed, Spielberg stages it with great verve and tension. It's a cliffhanger.

I think it curious that Kushner and Spielberg refrain from showing Lincoln's assassination (I guess they don't want to give anybody ideas). But there is a scene where they tease the audience with it, which I don't think works. I am not an advocate of violence in movies, and there is no shortage of the violent face of war in this film, but violence is a particularly American predilection, and this demureness, although dignified, takes away from the political historical resonance that Kushner so skillfully embroiders. The murder of president Lincoln doesn't come as a shock, as it should; it comes as an afterthought. However, the characterization of Lincoln is so magnificent that it makes his assassination horribly tragic to contemplate, as close to the bone as when it has happened in more recent times to political figures like Martin Luther King or the Kennedys.

In the end, as we watch Lincoln, we cannot help but think that we just inaugurated a Black president's second term. Abraham Lincoln would be pleased. But this movie smartly avoids self-congratulation. In one scene, after the amendment is passed, Lincoln asks a Black woman if her people are ready for what is to come. He knows racial harmony is nowhere in sight. I did not understand her verbose response, but it is the question which we should ask ourselves again and again. Are we ready for what our rights and freedoms really mean, for keeping them, and defending them from those who hate them?

One cannot help but think after watching the thrilling crescendo of the results of the actual passage of the 13th Amendment, that it wasn't until the 1960s that Americans had to rise again to fight the deeply enduring racism of the South, and that even today we have racist taunts at our president and a society that still oppresses and profits unconscionably from Black, and now brown people, by sending them to jail in appalling numbers. Abraham Lincoln's work is not finished.

Nov 8, 2012

Rust And Bone

The great Jacques Audiard (Read My Lips, The Beat My Heart Skipped, A Prophet) has written (with Thomas Bidegain) and directed an intense story of two worlds that collide in the guise of the formidable Marion Cotillard and Matthias Schoenaerts (Bullhead). It is the love story of Stephanie and Ali, a reluctant couple that meets haphazardly at a club where he works as a bouncer and comes to her aid in a melee. They belong to a different class. She works as a whale trainer in Marineland, a tacky marine park in the south of France, and he's a troglodyte, a bit of a drifter with a 5-year old in tow, who is crashing at his sister's house. These two firmly believe in their own obstacles. She is the victim of a horrid accident, which makes her first depressed and then brittle and scared of love, and he is a royal fuck up, a beast, unsentimental, primal and irresponsible. But somewhere beneath all that muscle, he has a decent heart (and the hots for her) and he becomes her friend. He gets her out of her rut almost without wanting to, by refusing to feed her self pity. And she slowly warms up to him, which is almost as painful as having another accident. They are both physically battered, and love doesn't make it any easier. Rust and Bone is the story of how they end up loving each other despite their best efforts. If this sounds trite, in the masterful hands of Audiard, it certainly isn't. He has the good sense to cast Cotillard, who is a monster actress. Cotillard takes us through the hell of Stephanie's life after her accident without sentimentality, with courage and absolute veracity. It is a totally restrained performance, porous, transparent and transcendent. At some point she reads Ali the riot act, and it's like she is training another whale. But as strong and commanding as she tries to be, he devastates her, because she is vulnerable to him, to his mystifying power. Matthias Schoenaerts is also fantastic as Ali, a giant child with vast reserves of anger he uses best to beat other boxers to a pulp. Schoenaerts is a phenomenon: he has the body of a monster truck, but a sweet, childish face, and he is a gifted actor. Together, the two are combustible, particularly since they are wary of each other. She is a bit haughty and keeps him at bay and he responds by being an alpha male, oblivious to manners, and utterly unwilling to show her pity. They keep crossing the boundaries they both set, afraid of falling in love, until they are too much in each other's lives.

Rust and Bone is an intense emotional experience, but not a histrionic one. Audiard's sensibility is more visceral and less intellectual than that of many of his French colleagues, and he is best at observing and portraying people's difficulty with their own emotions. Rust and Bone is adapted from a short story by Canadian writer Craig Davidson and features a great soundtrack with lots of pop songs in English, plus the elegant music of Alexandre Desplat, who does particularly good work in Audiard's films, here as reined in and as powerful as is everybody else in this stunning movie.

A Late Quartet

I could hear Christopher Walken recite the phone book and die a happy woman. It is wonderful to see him playing a character who is not a gangster or a parody of himself. Here, he plays a cellist in a string quartet who learns he has Parkinson's and decides to retire. The loss of his quiet authority wreaks havoc on the lives of the other members of the group, a splendid cast comprised of Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener and Mark Ivanir. Walken has always been a great actor, and he proves it with his performance here: a dignified, bewildered, mournful music professor, a recent widower, and a mensch. In lesser hands the story could be an obvious melodrama, but it is quite well written by Seth Grossman and Yaron Zilberman, and skillfully directed by Zilberman.

Beneath their rarefied veneer, these people have ego trips, insecurities and emotional needs like everybody else. The actors all anchor the drama in compelling human behavior. Seymour Hoffman never ceases to amaze with his capacity for creating realistic, multilayered characters. He plays, literally, the second fiddle, and he is tired of it. He wants to become first violin even though everyone agrees he's not right for the role. His pride is deeply hurt and he just keeps making things worse for everybody, but the writers give him a saving grace. He wants the group to take creative risks, to get out of their well oiled perfection demanded by the obsessive first violin (Mark Ivanir). Hoffman is married to Keener, whom he loves deeply and unrequitedly. She is great, as is Imogen Poots, who plays their gifted daughter, also a musician, spoiled by her parents and deeply resentful of having to compete with their professional lives. Some of the plot is predictable, but somehow the well structured story has room for some surprises. This classical music world is beautifully photographed by Frederick Elmes with a rich, warm palette. Tasteful yet emotionally credible, A Late Quartet is a very satisfying film.

This Must Be The Place

An interesting train wreck of a movie by Paolo Sorrentino, the film stars Sean Penn as Cheyenne, a washed out emo rocker who lives in a sad, grand mansion in Ireland (to avoid taxes) and is bored out of his meager wits, which seem to have been extinguished by a life of drug use. The main problem with the movie is Penn's performance, which as committed as it is, and not without flashes of humor and slyness, is too exaggerated to be believable. Penn makes Cheyenne a soft spoken mess, a too delicate spirit still wearing makeup and hideous eighties hair long past his expiration date, but he turns out to be wily once he finds a purpose in life. Cheyenne is depressed because his morose songs made a young fan commit suicide. His wife, the fantastic Frances McDormand, (despite her spirited performance, it's impossible to understand what she sees in him), tells him he needs to find something to do with his life. He decides to go to America to see his father, whom he hasn't talked to in thirty years. The father turns out to be an orthodox Jew and Holocaust survivor. Cheyenne learns that the Nazi who tortured him is still around, and goes on a quest to find him. His wispy façade conceals a man with a healthy force of will: the pathetic ex-rocker becomes a pretty effective Nazi headhunter. The movie is a moral fable about guilt and consequences, about children and parents, about people holding dark secrets that spread misery around like an invisible force field. What makes it fascinating is the contrast between its haunting sadness and Sorrentino's trademark crisp, hyperrealistic visual style (Luca Bigazzi is the cinematographer). The movie doesn't quite work, but you can't avert your eyes. Cheyenne goes from New York, where he confides in his friend David Byrne, playing himself, to the Southwest, to the Midwest, and I was bracing for the usual European filmmaker oversimplifying of America and its Marlboro country vistas, but Sorrentino is smarter than that. He doesn't caricature America or its people, he trains his stylish eye on its endless landscapes. The movie looks gorgeous.

Cheyenne's search leads him to the Nazi's granddaughter (a great Kerry Condon) and her chubby misfit of a son, and the three develop a tender friendship. This is the best part of the movie, the most quietly moving. The rest is tonally jarring, deeply unbalanced by a central performance that doesn't quite jell and a strained ending. But the music by David Byrne and Will Oldham is lovely and if you decide to go on the quirky ride, This Must Be The Place has, at moments, a certain amount of grace.

Nov 4, 2012

The Bay

Or nature's payback time. It is unfortunate that this environmental horror flick by Barry Levinson opened on the same week that Sandy ravaged the East Coast. There were exactly six people at the screening I saw (too soon?) but this movie deserves a much wider audience. It is in the vein of all those supposedly found footage screamers like the Paranormal Activity series, (same producers), but the difference is that there is a good director at the helm. You can see Barry Levinson's nimble hand in the great direction of actors and in the realistic delivery of dialogue, which is one of his trademarks. Usually these movies have wooden B-listers who can't act their way out of a paper bag. Nobody in The Bay is well known, but they are all solid character actors, and it makes a difference.

Now, I am past the point of exhaustion with the DIY camera horror flick genre, a la Blair Witch Project. Remember when one could be scared shitless without a cheapie iPhone or video camera shaking all over the place? Still, Barry Levinson uses every small camera known to man with panache, he has a sly sense of humor, and the movie, if not particularly suspenseful, is really icky. The gross out parts are fabulously gross. The Bay is an environmental horror movie, where people get horrible boils and something eats them from inside. It's enough to make everyone become an advocate for the Green Party.

How scary is it when the water you drink, bathe in and cook in is polluted with mutated organisms (courtesy of industrial agriculture, and literally, chicken shit) that eat you from the outside in? The Bay is a combination disaster and flesh eating bacteria movie. The plot (screenplay by Michael Wallach) is rather flimsy, and more could have been made about evil corporate interests in cahoots with politicians that suppress information about pollution. Although it has a couple of jumps, it delivers more atmosphere and heebie jeebies than suspense. It's the way the story is framed that blunts the panic. It is narrated by a survivor, to whom nothing really happens, which dulls the sense of urgency; the worst already happened. Even though the use of consumer cameras adds realism, it takes away scariness, because the camera never lingers long enough on anything or anyone to create a sense of menace. Too much jumping around. The equipment that records the mayhem adds an extra screen, and thus, distance, which in my view, makes it less scary. One misses the ominous gliding camera work of Kubrick or Polanski. The kind of point of view of being immersed in the action that makes your hair stand on end is sadly not present in this movie, although Levinson stages certain events off camera that are all the more disturbing for being out of sight.

The Bay is smart, as these movies go, but it could be smarter. Even though it takes place in a very small town in Maryland, it doesn't use the mass hysteria that could quickly be unleashed by twitter and the internet. The CDC and FEMA are portrayed as cumbersome, slow bureaucrats, while it would be more exciting if everybody actually freaked out and contributed to exacerbate the problem. The small community is cut off from the mainland, but we don't see how or by who. I imagine that a lot of this is due to a small budget (the reason why these films are so profitable and why they use mini cameras). Still, Levinson gets a lot of mileage out of his "found" footage. Particularly gleeful and effective are shot after shot of people splashing around, jumping in the water, swimming in the pool, (very reminiscent of the opening of Jaws), completely unaware of the poison that lurks beneath the surface. It's very American, to celebrate the 4th of July (as in Jaws) without a care in the world, oblivious to the fact that the damage we do to the Earth, even in this little All American town, is going to come back, according to this movie, to bite our tongues off.

Nov 3, 2012

Flight

We should have known not to have much faith in a Robert Zemeckis production. After all, this is the man who brought us Forrest Gump, a celebration of human stupidity and possibly the most insulting mainstream movie ever made. What made us think that his penchant for moralistic corn would be abated?

Flight promises to be, on the one hand, a cathartic ride on a plane nosediving out of the sky, and on the other, a movie whose main character, Captain Whip Whittaker (straight from the Dept. of Heavy Handed Character Names) is a flawed hero with a moral dilemma. We did not expect it to be a manipulative, formulaic, queasily moralistic fable, which is not the same as a moral fable. Flight is moralistic in that cheap, hypocritical Hollywood way that turns an ethical dilemma into banal plot twists which not even the most innocent pollyanna can believe. The plane action is well done, but we expected more plane disaster excitement. Once that is over, the thrill is gone.

If there are saving graces, they are provided by the actors, particularly by Denzel Washington, who delivers a suave, totally credible performance as a highly arrogant and extremely gifted pilot. His arrogance feels multidimensional, and one roots for him despite it. He is fun as long as he drinks, and Washington makes Whip appealingly flinty, suspicious of God freaks. Somehow he doesn't alienate the audience, despite the movie jerking the viewer around over two hours with his inability to stop boozing, for no good reason.

John Goodman is there to deliver comic relief, in a similar role as the one that immortalized him in The Big Lebowski. He does it beautifully. Don Cheadle, Bruce Greenwood and Melissa Leo deliver the goods, and raise the level of what otherwise would be a Lifetime special. Character actors Tamara Tunie, Brian Geraghty and Peter Gerety (always wonderful) bring up the rear in style. There is one great scene in which Whittaker goes on a bender and he needs to clean up fast. One's hopes for the movie rise, thinking that it may flee out of the worn and predictable and deliver a more ironic, jaundiced outcome. But no such luck: we are taken to a place that seems real and exciting only to be plunged again into a tired narrative of humiliating self-redemption. Whittaker cannot be a hero unless he confesses to all his sins and finally accepts he's a drunk. He has to be punished for his excesses. This is not fun. This is a movie that only the Temperance Society can cheer for. It feels like a teetotaling pamphlet from the 1950s. And it bandies God and faith around so much, but not even in an honest, straightforward way, that I thought it was underwritten by televangelists. It's a movie that should have been made under a Romney regime. It feels that fake and old fashioned.

The shoddy script by John Gatins includes an utterly unnecessary love story between Whittaker and a heroin junkie (overacted by Kelly Reilly), and many bad lines of dialogue, such as "My name is Trevor. You saved my mother's life", uttered by a 10 year-old kid. I was riveted by Denzel at all times, but my eyes were rolling so much and so fast at the pat pieties and the leaden cliches, they must have looked just like that plane, upside down.

Nov 2, 2012

Holy Motors

Another example of French cheesy pretentiousness (or pretentious cheesiness), which garnered inexplicably good reviews, this film by Leos Carax is a high concept bonbon. Alex, an unsmiling Denis Lavant, goes in a white limo to several appointments through Paris. In each appointment he disguises himself as a character (the makeup design is spectacular): a poor old female beggar, a businessman, a crazy imp who scares people at the Pere Lachaise cemetery. The idea is that people do not want to see their stories on screens anymore. They want them to be as real as possible, in front of their eyes. The screens keep getting smaller, so actors like Alex go from one assignment to the other creating stories. It's a nifty concept, allright, and one of the rare instances I wish Hollywood (Spielberg, Zemeckis, or even better, Spike Jonze, say) would borrow it and make a much more entertaining movie out of it.

At least the cheese would not have intellectual airs; it would have more pizzazz.

The problem is the humorless, unimaginative execution. The grandiose tackiness keeps mounting, as in a vulgar sequence where the imp kidnaps "supermodel" Eva Mendez (such a good sport, and so wasted), and brings her to a cave, showing his prosthetic erection - very distracting as you might imagine - and fashions a burqa to cover her, a mortal sin, as far as I'm concerned. But there is no rhyme nor reason for this or any other story. It's all in Carax's head: clunky, obvious, juvenile and self-important.

Some moments are meant to evoke magic. The liveliest is an "intermission" in which Lavant plays an accordion followed by a merry band of players inside a church. Nice steadicam work. The rest is not as adeptly staged. An extended sequence inside the abandoned La Samaritaine department store, featuring Kylie Minogue (!), for instance, aims for melancholy, but it's rather drab. The whole movie looks opaque and tired, not very inspired, like poor Alex.

Still, Lavant is riveting as he applies and takes off his amazing makeup jobs. He is obviously versatile. He has the body of a dancer or a circus performer, and he becomes all these characters, none of which has a sense of humor. There is an inkling of the magical, sacred work that actors do, how their work may affect their feelings, as well as ours, but the stories are mostly preposterous and not emotionally engaging. In fact, it's the random ridiculousness of the stories, and the heavy handed attempt at some sort of surrealism, that makes Holy Motors exasperating. Only for those with a high tolerance for French cheese.

Oct 21, 2012

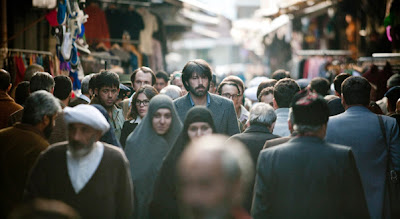

Argo

It's a great story, very well told by director/protagonist Ben Affleck, based on the true story of Tony Mendez, who concocted a fake film production in order to rescue out of Iran six American embassy employees who were hiding in the house of the Canadian ambassador, at the time of the Iranian hostage crisis.

The movie starts with a lovely, powerful sequence with storyboards that remind us of that once upon a time, there was a democratically elected Iranian leader, a secular man, who decided to nationalize his country's oil industry. In no time, the US and Britain engineered a coup d'etat and in his place put the Shah Reza Pahlavi, who became a monstrous murderer, thief and torturer. It was this intervention that helped create the Islamic Revolution which deposed the Shah, who was granted asylum in the US and never extradited as his the new regime in Iran justly requested. Today we have to deal with these fundamentalist maniacs thanks to our stellar foreign relations fiascoes such as that one. Times were so different then, before our middle eastern misadventures escalated into 9/11, Iraq and Afghanistan, that it was not inconceivable that producers would want to go shoot a film in Iran just as the Revolution was happening. But truth is stranger than fiction.

Affleck plays Mendez, a stonefaced agent specializing in exfiltration (getting people out of messes), who gets the idea to use a fake movie as a cover, when no other cover will hold. There is much enjoyment to be had in the casting of the great John Goodman as the make up effects artist and CIA helper John Chambers, who helps put the fake production together and the marvelous Alan Arkin as Lester Siegel, an old Hollywood shark. Re Alan Arkin all one can say is that nobody in the business lands their lines with such deadpan aplomb. Everything that comes out of his mouth has perfect, devastating timing. Everything has a delicious zing. Goodman is on screen for like five minutes and almost steals the show. But it is the handling of the material that is most interesting. There is nothing funny about the first part of the movie. The violence is palpable, the hatred of America shot in close up (stellar, unobtrusive, but exciting work by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto), the nerves are frayed. But the moment the Hollywood plan turns up, comedy does too and one wonders if Affleck is going to be able to mesh the tones. Somehow, it works. All the actors are excellent, the jokes land well (except for one they keep repeating over and over), and the movie is very well done, the pacing exciting, the experience thrilling. Affleck is becoming a more confident director with each movie he makes. He greatly underplays plays Mendez as a dry man who is loath to betray feelings. His wooden face as he sits in a negotiation between Arkin and Richard Kind is hilarious. He betrays nothing except for a minuscule flick of recognition, perhaps awe, when Arkin mentions his friend Warren Beatty. This CIA man feels more alien in this meeting than perhaps in any other of his dangerous missions, but he too is impressed by star power. The third act is a nail-biting bit of suspense, including soaring string music (by Alexandre Desplat), just like in the movies, as if to weave the surrealism of the actual story with the fantasy of film. A bit where the fake filmmakers show some Revolutionary guards at the airport the film's storyboards and one of them literally pitches the movie to them in Farsi, with impropmtu sound effects, speaks to the power that stories, and movies, even the most farfetched and ridiculous, have to enthrall an audience. Argo ends too neatly, too happily, like in the movies. It is more of a caper with political sting than an issue movie and it errs on the side of telling a good story, even if it takes liberties, and cuts to the chase, like they do in the movies.

Oct 17, 2012

NYFF 2012: No

This third part of Pablo Larraín's trilogy about Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile is the most approachable and crowd pleasing of them all, if not the most rigorous. The movie that put him on the map, Tony Manero, is a carefully crafted, extremely disturbing look at a sociopathic character, played by the fantastic Alfredo Castro, who is obsessed with impersonating John Travolta at a time when his countrymen are being murdered and tortured. His second movie, Post-Mortem, also starring Castro, is also an unsavory tale about a weird man who is confronted by the ugly reality of his country as his job at the morgue becomes too busy. Throughout the trilogy, Larraín seems consumed by the idea of individual indifference in the face of tyranny.

This final installment, based on a play by Antonio Skármeta, and co-written by Pedro Peirano, the writer director of The Maid and Old Cats), follows the travails of advertising creative René Saavedra (a wonderful Gael García Bernal), as he reluctantly decides to help the Chilean opposition craft a TV campaign in order to win a referendum in the last years of that brutal regime. The US, after helping Pinochet gain power by orchestrating a coup d'etat against Salvador Allende, got qualms about the human rights abuses of Pinochet's 15-year dictatorship and pressured for a referendum, the first democratic elections to take place in that country since Pinochet took power. The movie is a fun, although rambling tour into how the opposing campaigns communicated to the Chilean people. "No" means the vote against Pinochet for another term.

Larraín, who has a penchant for stylishly ugly aesthetics, goes all the way by shooting the entire movie in low resolution video, which is what existed in those days. After a while, one gets used to the result, but everything looks hideous. However, this time he stays away from the ugly, violent grotesquerie of his other two films.

René's boss is a Pinochet sympathizer and rich bastard, played by the chamaleonlike Castro, whose agency helps the regime, because he actually supports it ideologically. It's a fun fight between two creative minds, and not necessarily between opposing ideologies, but between young and fresh, and conservative and hanging on to power by whatever means possible. René's boss likes to threaten and harass, much like the regime he represents.

Larraín gets the dynamics and milieu of advertising just right. Very much fun is watching René always use the same bullshit spiel ("Chilean society is ready for this") to sell different campaigns to different clients, regardless of the product. He is not concerned with ideology. He cares about image and fun looking spectacle and the kind of idiotic ads that somehow move a lot of product. The movie starts with an outrageous commercial for a cola called "Free", so hilariously tacky that not even an imaginative director like Larraín could have come up with it as a parody. Larraín uses actual footage of brutally squelched demonstrations, Pinochet ads, opposition ads, and the commercials of the era and intersperses them with the story of René, in which actual leaders of the opposition movement appear, including Patricio Aylwin, the man who eventually won the election. The choice to unify the quality of the video to the actual footage pays off, even as one's eyes suffer, making the movie seem as real and in the historic moment as possible.

René fights the tendency of the opposition to sound like martyrs and recite the catalogue of horrors under Pinochet's murderous regime. He instinctively understands that even though it may all be true, people don't want to hear it. It dispirits them and makes them afraid to vote against such a well oiled repressive machine. Instead, he fights Pinochet with rainbows, young people dancing on the streets and Chileans eating baguettes at picnics (unrealistic, but it looks pretty, which is what matters). His clients feel this is offensive, but what choice do they have? Since the law is that each party has 15 minutes a night (an eternity) to present a platform, the No party allows René to do his rainbows and "We are the world" ripoffs, but they also sneak in some powerful truth telling ads. Meanwhile, on the other side, the debate hinges upon whether the Generalissimo should always appear in his medal bedecked uniform or wear civilian clothes. When they decide to poke fun at the rainbows and the happy dancing, it backfires, since as René knows, the audience hates negative reinforcement. As he sees himself losing the battle against frivolity and optimism, René's boss bitterly muses that the "Yes" campaign has too many military men, too many fat military wives, too many parades and uniforms. It is as stale and putrid as can be, as befits where it comes from.

Larrain is a great satirist and in No he lets loose and spends a lot of time going from one campaign to the other, and including a lot of fascinating original footage, but which unfortunately makes the energy of the movie flag. Still, No is a very engaging, original, smart film about a man that ends up doing something heroic for his country without really wanting to; an unlikely hero without principles, except that of doing what he knows to do best. García Bernal's stunned reaction to the results of the election, his gradual overcoming with emotion as he goes out into the streets anonymously and the enormity of what happened seeps in, is a gorgeous piece of silent acting. There is great joy at Pinochet's defeat but the movie ends in a bittersweet note as René goes back to selling bullshit, a changed man. The question is whether Chile has really changed with him.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)